Abstract: The widespread use of antimicrobial mouthwashes highlights the importance of understanding their impact on both clinical outcomes and the oral microbiome. This literature review seeks to critically evaluate the current academic knowledge regarding the clinical efficacy of mouthwash containing cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) and zinc lactate in reducing plaque, gingivitis, and oral malodor, with a particular focus on its interactions with the oral microbiome. Clinical trials have validated the efficacy of CPC and zinc lactate in enhancing oral health metrics, although the long-term impact of their combined use on the oral microbiome warrants further exploration. CPC and zinc lactate in a mouthwash is particularly effective against oral biofilms. While bacteria has the potential to develop resistance against antiseptics, there is no evidence at this time to suggest that CPC and zinc lactate influences resistance in the oral cavity. However, there is evidence that CPC and zinc lactate in combination may be superior to other antibacterial mouthwashes at controlling periodontal pathogens while promoting a healthy and balanced oral microbiome. Future research should prioritize longitudinal, multi-omics investigations to elucidate the nature and extent of these interactions across diverse bacterial communities. The capacity of CPC and zinc lactate to support a healthy oral microbiome, without promoting antimicrobial resistance, underscores their combined potential as a safe and effective oral hygiene solution.

Maintaining optimal oral hygiene is a critical aspect of overall health, serving as the primary defense against an array of oral diseases, including dental caries, gingivitis, and periodontitis.1 The significance of controlling plaque—the bacterial biofilm that forms on teeth—is supported across the literature as having positive impacts on oral health outcomes.2 While mechanical plaque disruption through regular toothbrushing and flossing is considered to be the foundation of oral hygiene, its effectiveness can be limited by the topography of the oral cavity, individual dexterity, and personal practice.3 To overcome these limitations and to access hard-to-reach areas within the oral cavity, such as interproximal spaces, mouthwashes serve as adjunctive therapies.4 Their usage has seen an increase worldwide, reflecting a growing awareness of their potential benefits.5 Mouthwashes offer such advantages as dental plaque reduction, control of gingival inflammation, and mitigation of oral malodor.4

The oral microbiome, a diverse ecosystem of microorganisms that reside within the oral cavity, plays a vital role in the maintenance of oral health and overall systemic health.6 A balanced microbiome acts as a natural defense against the colonization of pathogenic microorganisms, and imbalances can lead to localized oral diseases like dental caries and gingivitis as well as systemic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases, gastrointestinal diseases, and neurological disorders.6 Consequently, understanding how the ingredients in mouthwash formulations interact with microbial balance is important when evaluating the overall impact of oral hygiene products.

Widely used in mouthwashes for its broad-spectrum antiseptic properties, cetylpyridinium chloride (CPC) is a monocationic quaternary ammonium compound capable of disrupting bacterial cell membranes and interfering with essential bacterial metabolic processes.7,8 The amphiphilic nature of CPC’s structure allows for an electrostatic interaction with negatively charged bacterial surfaces.9 The positive pyridine head displaces cations on the membrane and the hexadecane tail inserts into the lipid bilayer, disorganizing the bacterial membrane and causing leakage of cellular components.8 CPC’s surfactant properties allow for even distribution of the liquid within the oral cavity regardless of surface irregularities.8 Clinical studies show CPC’s activity against the oral pathogens linked to periodontal disease and its bactericidal effects on oral biofilms.10

Zinc salts, including zinc lactate, are commonly added to oral hygiene products because of, most notably, their involvement in the reduction of oral malodor.11 Zinc ions inhibit the formation of volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) due to their strong affinity for the thiol groups within VSCs.12 When zinc ions interact with these sulfur-containing molecules, they form insoluble odorless sulfides.12 Additionally, the inclusion of zinc in mouthwash formulas has shown to enhance long-term antibacterial activity and inhibit bacterial metabolism.13

Therefore, the rationale for combining CPC and zinc lactate in a single mouthwash formulation (CPC + Zn) stems from the concept of harnessing their individual strengths with the intention of achieving a comprehensive oral hygiene product that effectively targets plaque, gingivitis, and halitosis. This review seeks to synthesize the current academic knowledge regarding the clinical efficacy of mouthwash containing both CPC and zinc lactate, with a particular focus on its interactions with the oral microbiome.

Clinical Efficacy of CPC and Zinc Lactate Mouthwash

Several clinical trials have provided evidence for the superior antiplaque and antigingivitis efficacy of mouthwash formulas containing CPC + Zn in comparison to fluoride-based mouthwash, CPC mouthwash, alcohol-free essential oil mouthwash, and essential oil mouthwash in an alcohol base. Two 3-month, parallel-group clinical studies evaluating the efficacy of mouthwash containing 0.075% CPC and 0.28% zinc lactate compared to mouthwash containing 0.02% sodium fluoride found that the CPC + Zn mouthwash provided significantly greater plaque control and reduction in gingival inflammation.14 The two clinical trials were conducted at Loma Linda University in California and an Oral Health Clinical Services site in New Jersey and reported very similar results. The groups that were treated with CPC + Zn mouthwash had a 20.6% and 21.5% greater reduction in whole-mouth gingivitis and a 27.4% and 25.3% greater reduction in whole-mouth plaque scores compared to the fluoride mouthwash groups in the California and New Jersey sites, respectively. Greater reductions in gingival severity, which is categorized as inflammation and bleeding, were also observed at both sites for the CPC + Zn group compared to the fluoride groups; however, the California site reported a 62.5% greater reduction and the New Jersey site reported a 38.6% greater reduction in gingival severity.

Additionally, two 6-week studies were conducted on the efficacy of 0.075% CPC and 0.28% zinc lactate compared to a 0.07% CPC mouthwash with no zinc lactate—one at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil and one at the Universidad Católica Santo Domingo in Dominican Republic.15,16 After 6 weeks of treatment, the CPC + Zn groups showed a 16.8% and 13.2% greater reduction in whole-mouth gingivitis and a 16.8% and 16.1% greater reduction in whole-mouth plaque index scores than the group treated with CPC alone at the Brazil and Dominican Republic sites, respectively. Clinicians at the two sites also reported greater reductions in gingival severity for the group treated with CPC + Zn compared to those treated with CPC alone: the Brazil site reported a 54.5% greater reduction and the Dominican Republic site reported a 28.6% greater reduction in gingival severity. The results of these studies suggest that the addition of zinc lactate to a CPC-based mouthwash formula enhances the antiplaque and antigingivitis effects of the product.

Essential oil–based mouthwashes are marketed with or without an alcohol base, and claims have been made that report equivalent control of plaque and gingivitis regardless of alcohol content.17-19 However, this evidence is ambiguous when evaluating the efficacy of these mouthwashes in comparison to mouthwashes containing CPC + Zn. A 6-week study comparing mouthwash with 0.075% CPC and 0.28% zinc lactate and alcohol-free essential oil mouthwash found that the CPC + Zn treatment significantly outperformed the essential oil mouthwash across all antiplaque and antigingivitis indices.20 CPC + Zn had a 26.7% greater reduction in whole-mouth plaque and a 10.6% greater reduction in whole-mouth gingivitis scores than the alcohol-free essential oils. However, in a 6-week clinical trial comparing mouthwash with 0.075% CPC and 0.28% zinc lactate and essential oil mouthwash with 21.6% ethanol, both mouthwash formulas significantly improved plaque and gingivitis scores for all timepoints compared to baseline.21 After 6 weeks, the CPC + Zn group exhibited a 37.2% reduction in plaque severity and 47.7% reduction in gingivitis severity, and the essential oils with alcohol group showed a 35.9% reduction in plaque severity and 38.6% reduction in gingivitis severity compared to baseline, resulting in no statistically significant difference measured between the two mouthwash treatments. Given that alcohol-based mouthwash has been associated with increased abundance of oral opportunistic bacteria and significantly impacts the oral microbiome,22 a CPC + Zn mouthwash is an effective alcohol-free alternative for plaque and gingivitis control.

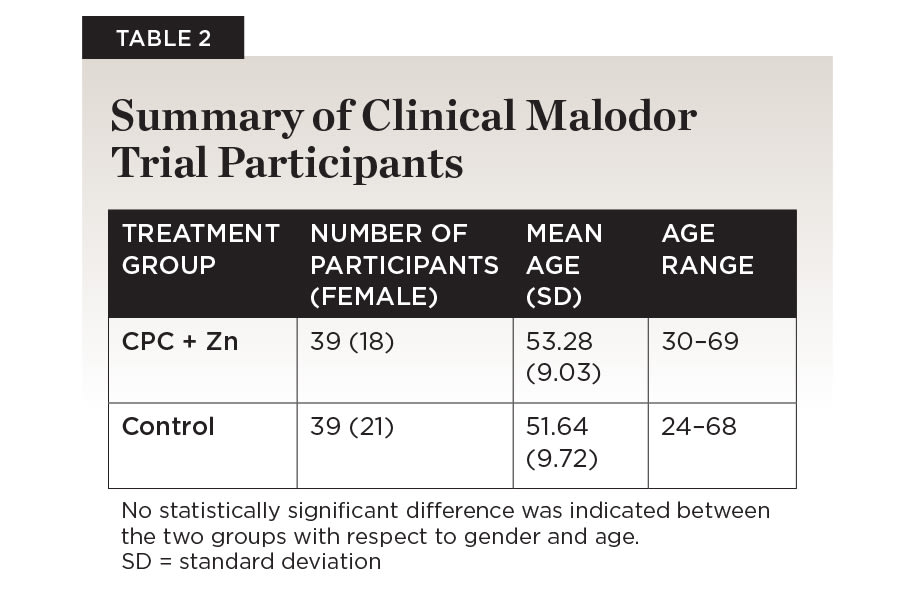

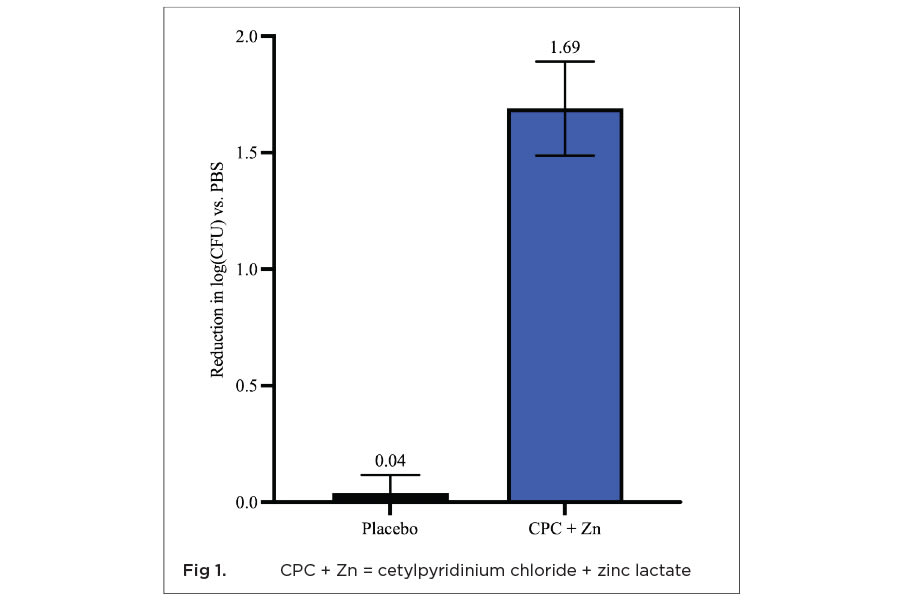

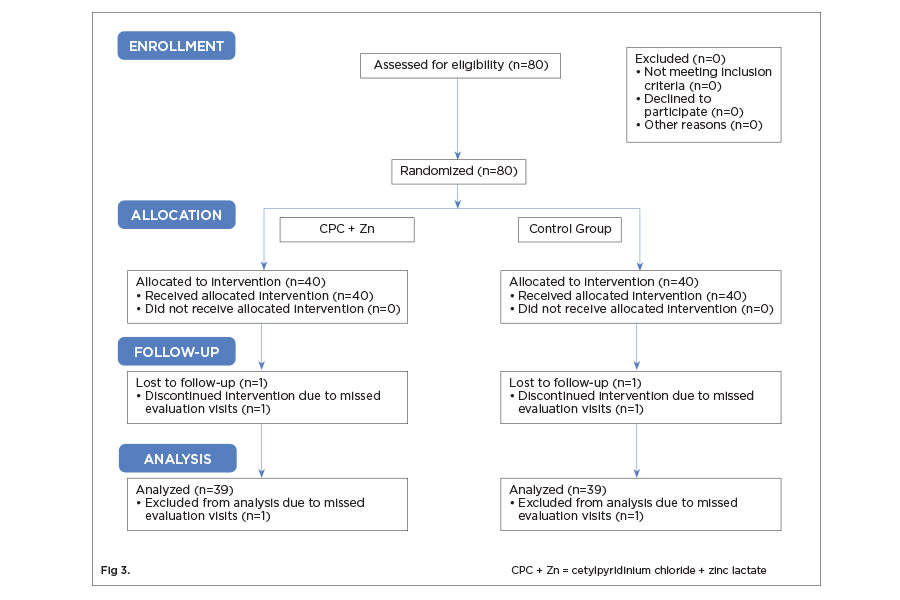

The CPC and zinc combination has also demonstrated efficacy in reducing aerosolized bacterial load, a promising finding. A randomized clinical trial evaluated the effect of a pre-procedural mouthwash containing 0.075% CPC and 0.28% zinc lactate on reducing bacteria in dental aerosols after ultrasonic scaling compared to chlorhexidine, water, and no rinsing.23 Notably, the results of this study indicated that the colony-forming units detected in the aerosols from the CPC + Zn group and the chlorhexidine group were statistically similar. Both mouthwashes resulted in significantly less aerosolized bacteria than when patients were treated with water or no rinsing. Chlorhexidine has known bactericidal efficacy and has been shown to reduce gingivitis and plaque across many clinical trials.24 While chlorhexidine is effective at targeting multispecies biofilms that include pathogenic bacteria like Streptococcus mitis and Porphrymonas gingivalis, it also decreases bacterial diversity, which one study found led to more acidic oral conditions in healthy individuals.25,26 This pre-procedural rinse study indicates that CPC + Zn is as effective as chlorhexidine in reducing the risk of infection during dental procedures and may be a better alternative for a balanced oral microbiome.

Intriguingly, a recent study evaluating the efficacy of gargling with mouthwash in preventing the development of respiratory symptoms suggests that adding a 0.075% CPC and 0.28% zinc lactate mouthwash to oral care regimens is beneficial in lowering the incidence of upper respiratory symptoms associated with cold and flu.27 Specifically, the study found that adding regular gargling with the CPC + Zn mouthwash to an oral care regimen resulted in a 21.5% decrease in respiratory symptoms and a 11% decrease in severity of symptoms compared to brushing alone.

This body of evidence underscores the effectiveness of mouthwash formulations containing CPC and zinc lactate as superior agents for managing plaque and gingivitis compared to other commonly used mouthwash formulas, including those based on fluoride, CPC alone, and essential oils, with or without alcohol. The studies consistently demonstrate the enhanced capability of CPC + Zn combinations in reducing plaque, gingival inflammation, bacterial load, and respiratory symptoms associated with cold and flu. Furthermore, given the potential adverse effects of alcohol-based mouthwashes on the oral microbiome, an alcohol-free option containing CPC and zinc lactate represents an effective and safer alternative for individuals seeking robust oral health benefits. These findings support the consideration of CPC and zinc lactate mouthwash as a preferred option in oral hygiene regimens aimed at reducing plaque and gingivitis.

CPC and Zinc Lactate Mouthwash and a Healthy Oral Microbiome

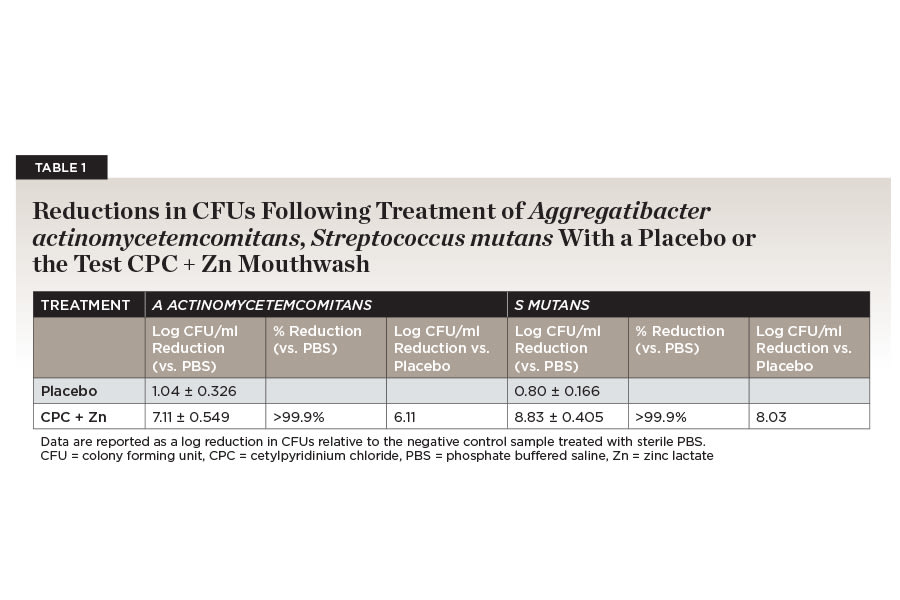

The combined action of CPC and zinc lactate in a mouthwash is particularly effective against oral biofilms. CPC has been shown to effectively inhibit the activity of bacterial glucosyltransferase, which is the enzyme responsible for synthesizing glucan, a key biofilm component.28 This biofilm-specific mechanism may be why CPC was also seen to have a 20% biofilm kill depth with static immersion into the mouthwash compared to the 5% kill depth seen with chlorhexidine immersion.8,29 Simultaneously, zinc’s ability to inhibit bacterial adhesion and weaken biofilm matrix could further enhance mouthwash efficacy against oral biofilms.30 The dual approach to targeting both microbial components and biofilm suggests a complementary action that is reflected in antimicrobial studies.

An in vitro biofilm study comparing mouthwash containing 0.075% CPC and 0.28% zinc lactate to a negative control with no active ingredients, mouthwash containing only 0.075% CPC, essential oil mouthwash, and mouthwash with essential oils in an alcohol base found that CPC + Zn continued to significantly reduce bacterial biofilm viability 2 and 5 hours post-treatment by 42.8% and 62.1% compared to negative control, respectively.31 It was the only mouthwash in the study that significantly reduced biofilm viability over time.

In conjunction with the antibacterial properties of CPC and zinc lactate, it is important to consider the impact of this mouthwash on a healthy oral microbiome. Disrupting the natural balance of the oral microbiome has the potential to lead to dysbiosis and, concerningly, antimicrobial resistance.32,33 It is possible for bacteria to develop resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds like CPC through upregulated efflux pumps, outer membrane alterations targeting binding sites, and biodegradation; however, there is no evidence to suggest that CPC is influencing resistance in the oral cavity.32 When comparing resistance to chlorhexidine in Enterococcus faecalis and Streptococcus mutans, it was observed that repeated exposure to chlorhexidine resulted in resistance in E faecalis, but no increased resistance to CPC was observed in either E faecalis or S mutans.34

Notably, a recent study evaluating the effects of mouthwash containing 0.075% CPC and 0.28% zinc lactate, mouthwash with 0.12% chlorhexidine, and 0.075% CPC mouthwash in a multispecies biofilm model found that all mouthwashes reduced metabolic activity, biofilm viability, and several species counts, including P gingivalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum, Parvimonas micra, Campylobacter gracilis, and S mutans.35 However, only the CPC + Zn combination reduced the pathogen Prevotella intermedia. The authors specifically highlight that P intermedia is associated with oral biofilm dysbiosis and reducing the species is integral to maintaining homeostasis.35 Perhaps most importantly, however, is the evidence that the CPC + Zn mouthwash did not disrupt the balance of health-associated bacterial species, while treatment with either chlorhexidine or CPC without zinc lactate reduced these species. These results suggest that CPC and zinc lactate in combination may be superior at controlling periodontal pathogens, while promoting a healthy and balanced oral microbiome.

These preliminary findings indicate that CPC and zinc lactate may act synergistically or additively to enhance antimicrobial activity against a range of oral pathogens and potentially modulate the biofilm environment in a way that is more favorable for oral health. However, future research should prioritize longitudinal, multi-omics investigations to elucidate the nature and extent of these interactions across the diverse bacterial species and communities within the oral microbiome. Understanding the specific impact on a wider range of bacterial species and their functional activities will be crucial for a comprehensive assessment of the combined effect of CPC and zinc lactate on oral health.

Conclusions

This comprehensive evaluation of the current literature on the impact of mouthwash containing CPC and zinc lactate on oral heath underscores its ability to effectively reduce plaque accumulation, gingival inflammation, and oral malodor. The additive antimicrobial properties of CPC + Zn allow for sustained antibacterial action and effective control of oral malodor, while minimizing the disruption of the oral microbiome. Clinical trials show that the addition of zinc lactate to a CPC-based mouthwash formula may enhance the antiplaque and antigingivitis effects of the product, outperforming essential oil mouthwashes and showing parity with alcohol-based mouthwash. Given that alcohol-based mouthwash significantly impacts the oral microbiome, CPC + Zn mouthwash may be an effective alcohol-free alternative for plaque and gingivitis control. It was also observed that CPC + Zn is as effective as chlorhexidine in reducing the risk of infection during dental procedures. Additionally, the capacity of CPC + Zn to support a healthy oral microbiome, without promoting bacterial resistance, underscores the combination as a safe and effective oral hygiene solution. Overall, these findings advocate for the adoption of CPC and zinc lactate mouthwash as an effective adjunctive to oral care strategies.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Meghan A. Berryman, PhD

Scientific Communications Specialist, Colgate-Palmolive Co., Piscataway, New Jersey

References

1. Axelsson P, Nyström B, Lindhe J. The long-term effect of a plaque control program on tooth mortality, caries and periodontal disease in adults. Results after 30 years of maintenance. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31(9):749-757.

2. World Economic Forum. The Economic Rationale for a Global Commitment to Invest in Oral Health. May 2024. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Economic_Rationale_for_a_Global_Commitment_to_Invest_in_Oral_Health_2024.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2025.

3. Milleman K, Milleman J, Bosma ML, et al. Role of manual dexterity on mechanical and chemotherapeutic oral hygiene regimens. J Dent Hyg. 2022;96(3):35-45.

4. Mouthrinse (Mouthwash). American Dental Association website. Updated December 1, 2021. https://www.ada.org/resources/ada-library/oral-health-topics/mouthrinse-mouthwash. Accessed July 15, 2025.

5. Montenegro MM, Flores MF, Colussi PRG, et al. Factors associated with self-reported use of mouthwashes in southern Brazil in 1996 and 2009. Int J Dent Hyg. 2014;12(2):103-107.

6. Rajasekaran JJ, Krishnamurthy HK, Bosco J, et al. Oral microbiome: a review of its impact on oral and systemic health. Microorganisms. 2024;12(9):1797.

7. Brookes Z, McGrath C, McCullough M. Antimicrobial mouthwashes: an overview of mechanisms – what do we still need to know? Int Dent J. 2023;73 suppl 2(suppl 2):S64-S68.

8. Mao X, Auer DL, Buchalla W, et al. Cetylpyridinium chloride: mechanism of action, antimicrobial efficacy in biofilms, and potential risks of resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64(8):e00576-20.

9. Dumitrel SI, Matichescu A, Dinu S, et al. New insights regarding the use of relevant synthetic compounds in dentistry. Molecules. 2024;29(16):3802.

10. Langa GPJ, Muniz FWMG, Costa RDSA, et al. The effect of cetylpyridinium chloride mouthrinse as adjunct to toothbrushing compared to placebo on interproximal plaque and gingival inflammation – a systematic review with meta-analyses. Clin Oral Investig. 2021;25(2):745-757.

11. Uwitonze AM, Ojeh N, Murererehe J, et al. Zinc adequacy is essential for the maintenance of optimal oral health. Nutrients. 2020;12(4):949.

12. Suzuki N, Nakano Y, Watanabe T, et al. Two mechanisms of oral malodor inhibition by zinc ions. J Appl Oral Sci. 2018;26:e20170161.

13. Schaeffer LM, Yang Y, Daep C, et al. Antibacterial and oral tissue effectiveness of a mouthwash with a novel active system of amine + zinc lactate + fluoride. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2024;10(4):e874.

14. Nathoo S, Li Y, Westphal C, et al. Efficacy of a mouthwash containing cetylpyridinium chloride and zinc on plaque and gingivitis reduction. J Dent Res. 2023;102(spec iss B):0316.

15. Rösing CK, Cavagni J, Gaio EJ, et al. Efficacy of two mouthwashes with cetylpyridinium chloride: a controlled randomized clinical trial. Braz Oral Res. 2017;31:e47.

16. Stewart B, García-Godoya B, Mateo LR, et al. Mouthwash containing cetylpyridinium chloride and zinc lactate shows enhanced antiplaque and antigingivitis efficacy. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2025;46 suppl 2:17-24.

17. Lynch MC, Cortelli SC, McGuire JA, et al. The effects of essential oil mouthrinses with or without alcohol on plaque and gingivitis: a randomized controlled clinical study. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18(1):6.

18. Bosma ML, McGuire JA, DelSasso A, et al. Efficacy of flossing and mouth rinsing regimens on plaque and gingivitis: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):178.

19. Min K, Glowacki AJ, Bosma ML, et al. Quantitative analysis of the effects of essential oil mouthrinses on clinical plaque microbiome: a parallel-group, randomized trial. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):578.

20. Langa GPJ, Cavagni J, Muniz FWMG, et al. Antiplaque and antigingivitis efficacy of cetylpyridinium chloride with zinc lactate compared with essential oil mouthrinses: randomized clinical trial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152(2):105-114.

21. Stewart B, García-Godoy B, Dillon R, et al. Antiplaque and antigingivitis efficacy of mouthwash containing cetylpyridinium chloride and zinc lactate compared to essential oils with alcohol. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2025;46 suppl 2:25-33.

22. Laumen JGE, Van Dijck C, Manoharan-Basil SS, et al. The effect of daily usage of Listerine Cool Mint mouthwash on the oropharyngeal microbiome: a substudy of the PReGo trial. J Med Microbiol. 2024;73(6).

23. Retamal-Valdes B, Soares GM, Stewart B, et al. Effectiveness of a pre-procedural mouthwash in reducing bacteria in dental aerosols: randomized clinical trial. Braz Oral Res. 2017;31:e21.

24. James P, Worthington HV, Parnell C, et al. Chlorhexidine mouthrinse as an adjunctive treatment for gingival health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3(3):CD008676.

25. Bescos R, Ashworth A, Cutler C, et al. Effects of chlorhexidine mouthwash on the oral microbiome. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):5254.

26. Millhouse E, Jose A, Sherry L, et al. Development of an in vitro periodontal biofilm model for assessing antimicrobial and host modulatory effects of bioactive molecules. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:80.

27. Muniz FWMG, Casarin M, Pola NM, et al. Efficacy of regular gargling with a cetylpyridinium chloride plus zinc containing mouthwash can reduce upper respiratory symptoms. PLoS One. 2025;20(2):e0316807.

28. Furiga A, Dols-Lafargue M, Heyraud A, et al. Effect of antiplaque compounds and mouthrinses on the activity of glucosyltransferases from Streptococcus sobrinus and insoluble glucan production. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2008;23(5):391-400.

29. Fabbri S, Johnston DA, Rmaile A, et al. High-velocity microsprays enhance antimicrobial activity in Streptococcus mutans biofilms.

J Dent Res. 2016;95(13):1494-1500.

30. Steiger EL, Muelli JR, Braissant O, et al. Effect of divalent ions on cariogenic biofilm formation. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20(1):287.

31. Schaeffer L, Daep CA, Ahmed R, et al. Antibacterial and anti-malodor efficacy of a cetylpyridinium chloride and zinc lactate mouthwash. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2025;46 suppl 2:9-16.

32. Brookes Z, Teoh L, Cieplik F, Kumar P. Mouthwash effects on the oral microbiome: are they good, bad, or balanced? Int Dent J. 2023;73 suppl 2(suppl 2):S74-S81.

33. do Amaral GCLS, Hassan MA, Sloniak MC, et al. Effects of antimicrobial mouthwashes on the human oral microbiome: systematic review of controlled clinical trials. Int J Dent Hyg. 2023;21(1):128-140.

34. Kitagawa H, Izutani N, Kitagawa R, et al. Evolution of resistance to cationic biocides in Streptococcus mutans and Enterococcus faecalis. J Dent. 2016;47:18-22.

35. Torrez WB, Figueiredo LC, Santos TDS, et al. Incorporation of zinc into cetylpyridinium chloride mouthwash affects the composition of multispecies biofilms. Biofouling. 2023;39(1):1-7.