Sean Lee, DDS; Yiming Li, DDS, PhD, MSD; Luis R. Mateo, MA; Guofeng Xu, PhD; Carl P. Myers, PhD; Divino Rajah, BS, MRA; Nicky Li, DMD, MPH; and Yun-Po Zhang, PhD, DDS (Hon)

Abstract: Background: The objective of this randomized controlled trial was the comparison of a stannous fluoride (SnF2) dentifrice stabilized with nitrate and phosphates (test) to a regular fluoride dentifrice (negative control) for the control of plaque and gingivitis over 6 months. Methods: A total of 80 adult participants were enrolled in this study that was conducted in Loma Linda, California. After randomization and blinding of study personnel and patients, enrolled participants were provided instructions for the use of their assigned dentifrice. At three visits (0, 3, and 6 months), various gingival and plaque indices were collected to determine the clinical efficacy of the SnF2 stabilized dentifrice. These results were compared with the results of the negative control dentifrice. Results: A total of 77 participants completed the study. The test dentifrice demonstrated statistically significant reductions versus baseline in all plaque and gingivitis indices after 3 and 6 months of product use. The negative control dentifrice demonstrated significant reductions versus baseline in all plaque indices, but not gingivitis indices, after 3 months of product use and in all plaque and gingivitis indices after 6 months of product use, with the exception of the interproximal gingivitis index, which did not reach statistical significance. The test SnF2 dentifrice showed statistically significant reductions in all plaque and gingivitis indices compared to baseline and to the negative control dentifrice after 3 months and 6 months of product use (all: P < .001). Conclusions: The results of this clinical trial showed statistically significantly improved clinical outcomes for reduction of gingival inflammation and improvement in plaque control over 6 months when using a new SnF2 dentifrice stabilized with nitrate and phosphates as compared to the results from a regular fluoride dentifrice. Practical Implications: This newly formulated SnF2 dentifrice may be of benefit to patients who need help controlling plaque biofilm and in reducing gingivitis, leading to an improvement in overall oral health.

Individuals with gum disease, or periodontal disease (PD), have an inflammatory condition that includes gingivitis and periodontitis. Gingivitis is the mildest form of PD,1 and as the population ages, it is expected that more cases of gingivitis will occur. PD impacts approximately 40% of adults and 60% of those over 65 years of age,2 although children can also be affected by PD.3,4 By 2030, all members of the "baby boomer" generation will have turned 65 years of age and will represent one out of every five Americans.5 This acceleration of the aging population is also seen globally with 10% of the global population older than 65 years of age in 2022, and this percentage is expected to increase to 16% by 2050 and 24% by 2100.6

Gum disease is a public health issue due to its high prevalence and the potential for significant health impacts. The burden of PD on healthcare systems is considered substantial, with high costs associated with treatment and lost productivity.7 Furthermore, it is becoming increasingly evident that there is a connection between PD and systemic health with the following diseases implicated: cardiovascular disease, diabetes, gastrointestinal disease, Alzheimer's disease, respiratory infections, and others.8,9 Therefore, it is important that effective strategies to prevent and treat gingivitis are available so that it does not develop into the more serious form of gum disease, periodontitis.

Stannous fluoride (SnF2) dentifrices are known to provide consumers with multiple benefits, including assisting with the reduction of plaque bacteria,10,11 reducing gingivitis,12,13 aiding in relief of dental hypersensitivity,14 and providing caries control.15 The oral biofilm known as dental plaque is the cause of oral diseases such as caries, gingivitis, and periodontitis.16 Ideally, toothbrushing would result in the complete removal of this oral biofilm. However, complete mechanical removal is not possible, and antibacterial agents such as SnF2 can be incorporated into a dentifrice to improve the overall efficacy of biofilm control.12,13

Maintaining bioavailable stannous fluoride within dentifrice formulations has been a challenge because Sn2+ easily hydrolyzes and oxidizes and precipitates in water and oxygen-containing environments, decreasing its therapeutic efficacy. Recently, stannous fluoride was combined with nitrate and phosphates (SNaP), resulting in an improvement to both oxidative stability and solubility and, therefore, stannous bioavailability.17

This new dentifrice has undergone a series of laboratory and clinical tests to establish its efficacy and benefits to ensure that this new stabilization strategy has not compromised the antiplaque, antigingivitis, or other benefits offered by the dentifrice.10,18-20 In this study, the test dentifrice, containing 0.454% stannous fluoride stabilized with nitrate and phosphates, was compared to a negative control dentifrice, which was a regular commercial dentifrice with 0.76% sodium monofluorophosphate, in a 6-month study to evaluate the performance of both dentifrices against dental plaque and gingivitis.

Material and Methods

Study Design

The sample size of 80 participants (40 per treatment group) was determined based on the standard deviation for the response measures of 0.58, a significance level of α = 0.05, a 10% attrition rate, and an 80% level of power. This study was powered to detect a minimal statistically significant difference between study group means of 15%. The sample size calculation was based on historical data from a previous study.21 This randomized, single-center, double-blind, parallel-group study included 80 participants. The dentifrices compared were the test dentifrice, SNaP, and the negative control dentifrice, a 0.76% sodium monofluorophosphate dentifrice. Both were manufactured by Colgate-Palmolive Co. (colgatepalmolive.com).

This was a double-blinded study with neither the participants nor study personnel involved in participant evaluation (including the dental examiner) aware of the identity of the products or which treatment a participant was receiving. The test products were distributed and accounted for by personnel who were not involved with study participant evaluations.

Ethics

The study was reviewed and approved by the Loma Linda University Health Institutional Review Board (Loma Linda, California). All participants signed an informed consent form.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Participants who were between the ages of 18 and 70 (inclusive) and were available for the duration of the 6-month study were eligible to participate. They had to be in good general health and have at least 20 uncrowned permanent natural teeth, excluding third molars. In addition, eligible participants were required to have an initial mean gingival index score of at least 1.0 as determined by the Löe-Silness gingival index scale and index22 and an initial mean plaque index score of at least 1.5 as determined by the Turesky modification of the Quigley-Hein plaque index scale.23

Participants were excluded from the study if they had the presence of orthodontic bands, partial removable dentures, one or more tumors of the soft or hard oral cavity tissues, or any advanced PD (eg, purulent exudate, tooth mobility, or extensive loss of periodontal attachment or alveolar bone). Other exclusion criteria were the presence of five or more decayed carious lesions that required immediate restorative treatment, a history of allergies to oral care/personal care consumer products or their ingredients, or the use of any prescription medicines that might interfere with the study outcome. Participants were excluded if they had a history of alcohol or drug abuse, were pregnant or lactating women, or had an existing medical condition that would prohibit them from eating or drinking for up to 4 hours. Within the 2 weeks prior to the start of the study, participants were not allowed to use of any antibiotics, and within 1 month prior to the baseline examinations, participants were not allowed to receive a dental prophylaxis. Participants could not participate in any other clinical study or test panel within 1 month before entry into the study.

Clinical Examination and Instructions

Qualifying participants were randomized to one of the two study treatments based on their initial gingivitis and plaque scores using a computer-generated list of random numbers. After randomization, participants were provided with their assigned dentifrice and a soft-bristled adult toothbrush for use at home. They were instructed to brush their teeth using the provided toothbrush for 2 minutes in the morning and in the evening (ie, twice a day), using approximately 1.5 grams of their assigned dentifrice. No instructions were provided to the subjects regarding brushing technique. The dentifrices were supplied in their original tubes but were overwrapped with a white adhesive label to conceal the product's identity. Label information on each tube consisted of the study treatment code, the instructions for at-home use, and safety information, including emergency contact information. The examiner obtained adverse event information through oral examination as well as interviews with the study participants during each study visit.

Scoring Procedures

Gingivitis Assessment: The degree of gingival inflammation was determined by dividing each tooth into six surfaces, and the gingival index (GI) was scored as per the Löe-Silness gingival index.22 Subject-wise whole-mouth scores were calculated by summing all scores for all sites and dividing by the total number of assessed sites.

Gingival Severity: Only those sites that had GI scores of 2 or 3 at baseline were included in these calculations. The gingivitis severity index (GS) was determined by counting those sites and dividing by the total number of assessed sites.

Gingival Interproximal:The gingivitis interproximal index (Gint) score was determined by counting the scores from the mesiofacial, distofacial, mesiolingual, and distolingual surfaces of each tooth and dividing the sum by the total number of assessed sites.

Dental Plaque Assessment: A red dye solution was used to disclose plaque, and plaque index score (PI) was determined using the Turesky modification of the Quigley-Hein index.23 Subject-wise whole-mouth scores were calculated by summing all scores for all sites and dividing by the total number of assessed sites.

Plaque Severity:Only the distofacial, mesiolingual, and distolingual surfaces whose assigned PI scores were 3, 4, or 5 at baseline were included in these calculations. The plaque severity index (PS) was determined by counting those sites and dividing the sum by the total number of assessed sites.

Plaque Interproximal:The plaque interproximal index (Pint) score was determined by counting the scores calculated for each participant by adding the mesiofacial, distofacial, mesiolingual, and distolingual scores of each tooth and dividing the sum by the total number of assessed sites.

Statistical Analysis

For age and sex, independent t-tests and chi-squared tests were conducted, respectively. Statistical analyses were performed separately for the gingivitis assessments and dental plaque assessments. Comparisons of the treatment groups with respect to baseline gingival index scores and plaque index scores were performed using an analysis of variance (ANOVA). Within-treatment comparisons of the baseline versus 3-month and 6-month gingival and plaque index scores were performed using paired t-tests. Comparisons of the treatment groups with respect to baseline-adjusted gingival and plaque scores at the 3-month and 6-month examinations were performed using analyses of covariance (ANCOVA). All statistical tests of hypotheses were two-sided and employed a level of significance of α = 0.05.

Results

A CONSORT flow diagram indicates the numbers of individuals involved at the various stages of the study (Figure 1). A total of 80 participants were randomized into the study with 40 participants in each treatment group. Three participants, one in the test group and two in the negative control group, did not complete the 6-month study and were not included in the analyses. They did not present themselves at each follow-up visit as required. The treatment groups did not differ significantly with respect to age (P = .726) or sex (P = .565), as shown in Table 1. A summary of the race/ethnicity of the study population is presented in Table 2.

Baseline

Table 3 shows the mean values for each treatment at baseline, 3 months, and 6 months for each gingival and plaque indice. For all gingival-based indices and all plaque-based indices there were no statistically significant differences between the two treatments at baseline.

3-Month Follow-up

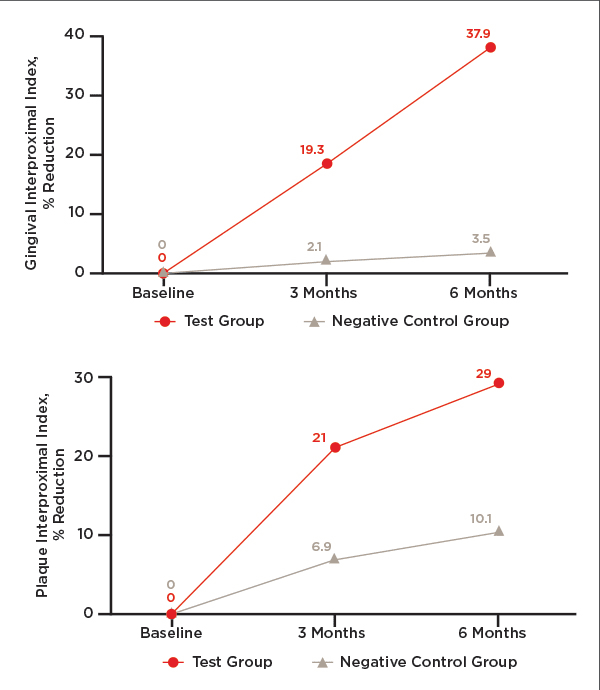

After twice per day toothbrushing with the assigned dentifrice, participants' gingival and plaque indices were measured at the 3-month follow-up visit as they were at the baseline visit. All indices for the test dentifrice showed a statistically significant reduction from baseline (Table 4). For the negative control dentifrice, all plaque indices showed a statistically significant reduction from baseline, while none of the gingival indices did (Table 4). Figure 2 through Figure 4 show the percentage reductions over time for each of the treatments relative to baseline.

The test dentifrice provided statistically significant reductions in all plaque and gingivitis indices in comparison to the negative control dentifrice (Table 4). These reductions ranged from 15.4% for the plaque interproximal index to 57.6% for the gingival severity index.

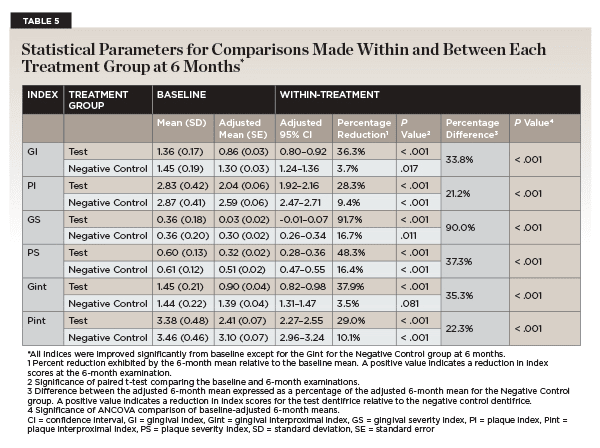

6-Month Follow-up

After 6 months of twice per day toothbrushing with the assigned dentifrice, participants' gingival and plaque indices showed similar trends to that observed after 3 months. As shown in Table 5, the test dentifrice provided significant reductions in all gingival and plaque indices as compared to their baseline values. On the other hand, the negative control dentifrice provided significant reductions as compared to baseline for all gingival and plaque indices, except for the gingival interproximal index. Figure 2 through Figure 4 show the percentage reductions over time for each of the treatments relative to baseline. For all indices, the percentage reductions relative to baseline are larger for the test dentifrice as compared to the negative control dentifrice.

The test dentifrice provided statistically significant reductions in all plaque and gingivitis indices in comparison to the negative control dentifrice (Table 5). These reductions ranged from 21.2% for the plaque index to 90% for the gingival severity index. For all indices, the percentage difference between the two dentifrices increased as a function of time.

Additional Analyses

Furthermore, 97.4% (38 out of 39) of the study participants who brushed with the test dentifrice showed improvement in GI at 3 months and 100% (39 out of 39) showed improvement at 6 months. Conversely, only 63.2% (24 out of 38) of the participants who brushed with the negative control dentifrice showed improvement at 3 months and at 6 months.

Safety Results

Throughout the study, no adverse events on the oral hard or soft tissues were observed by the examiner or reported by the participants when questioned.

Discussion

Periodontitis and gingivitis have been associated with a negative influence on oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL).24 Recent work by Broomhead et al on 27 trial participants with PD (15 with gingivitis and 12 with periodontitis) determined that gingivitis impacted the participants' overall quality of life.25 In particular, these individuals reported changing toothbrushes or their toothbrushing routines/techniques and avoiding chewy foods to prevent gum-related symptoms like bleeding, irritation, discomfort, and gum recession. Study participants switched to electric toothbrushes, which were perceived as more effective at tackling symptoms versus manual toothbrushes, and occasionally switched to softer toothbrushes to ease stress on the gums. Both groups also reported changes in brushing technique, becoming more vigilant with toothbrushing and avoiding brushing parts of their mouth due to the associated pain. The potential consequence of advancing gingivitis symptoms, fear of losing teeth, and feeling unhealthy or unclean were the most common perceived impacts. Study participants also reported avoiding laughing, covering their mouth, and using other methods to hide their symptoms in social situations. The authors concluded that "all gum health conditions should be considered in OHRQoL-related discussions."25 A recent workshop in Latin America recommended that health authorities develop "policies and programs for maintaining oral health and avoiding periodontitis through the effective management of gingivitis and promotion of healthy lifestyles at both population and individual levels."26 Thus, it is important that dentifrices be developed and evaluated with proven clinical efficacy against oral biofilm and gingivitis with the ultimate goal of patient acceptance and use.

A new SnF2 dentifrice stabilized with nitrate and phosphates was compared to a regular fluoride dentifrice in a phase III, single-center, double-blind, parallel-group randomized clinical trial that evaluated the control of dental plaque and gingivitis over a 6-month period. There were no significant differences between the participants in the two treatment groups with respect to age, sex, or baseline gingival health. The results showed that after 6 months of twice-daily brushing, all plaque and gingivitis indices improved relative to their baseline values for both the test dentifrice and the negative control dentifrice with the exception of the gingival interproximal index for the negative control dentifrice.

Previous studies have shown that twice-daily toothbrushing with a regular fluoride dentifrice improves gingival health by the removal of dental plaque and the concurrent reduction in gingivitis.12,13 Such is the case in this study as well with the negative control dentifrice demonstrating a reduction from baseline in almost all the plaque and gingivitis indices at 6 months. SNaP demonstrated a benefit beyond that of the regular fluoride dentifrice and was clinically proven to be significantly superior to the regular fluoride dentifrice in terms of the removal of dental plaque and the improvement in gingival health after 3 months and 6 months of twice-daily brushing as measured by all the plaque and gingival indices. Included in these results are the findings from hard-to-reach or interproximal areas in the oral cavity.

Finally, there was a substantial reduction of 90% in the gingival severity index (bleeding) for the test dentifrice as compared to the negative control dentifrice after 6 months' use. All participants using the test dentifrice showed improved gum health after 6 months. These findings along with the other studies10,18-20 in this current publication support the fact that SnF2 is both stable and bioavailable from this new 0.454% stannous fluoride dentifrice stabilized with nitrate and phosphates (SNaP technology), providing benefits in addressing many common oral care problems beyond those achieved by brushing with a regular fluoride dentifrice.

Conclusion

As compared to baseline and to a regular fluoride dentifrice, twice-daily brushing with a new 0.454% stannous fluoride dentifrice stabilized with nitrate and phosphates provides significant clinical benefit through the control of dental plaque and improvement of gingival health over 6 months. This SNaP dentifrice offers a new therapeutic and preventive option for dental practitioners to recommend to their patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Technical writing assistance was provided by Mack Morrison, PhD, of Starfish Scientific Solutions LLC. The author contributions were as follows: SL and YL: investigation, methodology, resources; LM: formal analysis; GX and CM: resources; DR and NL: conceptualization, supervision; YZ: conceptualization, funding acquisition. All authors contributed to writing, review, and editing.

DISCLOSURES

This clinical trial was supported by funding from Colgate-Palmolive Company. ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT06300866. The study was reviewed and approved by the Loma Linda University Health Institutional Review Board, Loma Linda, California. The authors YZ, GX, CM, NL, and DR are employees of Colgate-Palmolive Co. CM and GX have patents #US10918580B2 and #US11723846B2 issued to Colgate-Palmolive Co.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The documents containing the results of the research herein described are confidential. The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and/or its supplementary materials.

About the Authors

Sean Lee, DDS

Clinical Professor, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, California

Yiming Li, DDS, PhD, MSD

Distinguished Professor, Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, California

Luis R. Mateo, MA

President, LRM Statistical Consulting LLC, West Orange, New Jersey

Guofeng Xu, PhD

Senior Director Research and Development (R&D), Colgate-Palmolive Co., Piscataway, New Jersey

Carl P. Myers, PhD

Director R&D, Colgate-Palmolive Co., Piscataway, New Jersey

Divino Rajah, BS, MRA

Manager, Clinical Research, Colgate-Palmolive Co., Piscataway, New Jersey

Nicky Li, DMD, MPH

Technical Associate, Colgate-Palmolive Co., Piscataway, New Jersey

Yun-Po Zhang, PhD, DDS (Hon)

Senior Vice President and Distinguished Fellow, Clinical Research, Colgate-Palmolive Co., Piscataway, New Jersey

References

1. Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1809-1820.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Oral Health. About Periodontal (Gum) Disease. CDC website. May 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/oral-health/about/gum-periodontal-disease.html. Accessed October 2, 2024.

3. Alrayyes S, Hart TC. Periodontal disease in children. Dis Mon. 2011;57(4):184-191.

4. Reis AA, Paz HES, Monteiro MF, et al. Early manifestation of periodontal disease in children and its association with familial aggregation. J Dent Child (Chic). 2021;88(2):140-143.

5. Vespa J, Armstrong DM, Medina L. Demographic turning points for the United States: population projections for 2020 to 2060. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2020:25-1144.

6. United Nations. World population prospects 2022: summary of results. United Nations website. July 2022. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/World-Population-Prospects-2022. Accessed September 23, 2024.

7. The Economist Intelligence Unit. Time to take gum disease seriously: the societal and economic impact of periodontitis. Economist Impact website. Accessed May 3, 2024. https://impact.economist.com/perspectives/sites/default/files/eiu-efp-oralb-gum-disease.pdf. Accessed September 23, 2024.

8. Bui FQ, Almeida-da-Silva CLC, Huynh B, et al. Association between periodontal pathogens and systemic disease. Biomed J. 2019;42(1):27-35.

9. Martínez-García M, Hernández-Lemus E. Periodontal inflammation and systemic diseases: an overview. Front Physiol. 2021;12:709438.

10. Chakraborty B, Seriwatanachai D, Triratana T, et al. Antibacterial effects of a novel stannous fluoride toothpaste stabilized with nitrate and phosphates (SNaP): in vitro study and randomized controlled trial. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2024;45 suppl 3:12-20.

11. Haraszthy VI, Raylae CC, Sreenivasan PK. Antimicrobial effects of a stannous fluoride toothpaste in distinct oral microenvironments. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150(4S):S14-S24.

12. Hu D, Li X, Liu H, et al. Evaluation of a stabilized stannous fluoride dentifrice on dental plaque and gingivitis in a randomized controlled trial with 6-month follow-up [erratum in: J Am Dent Assoc.2019;150(4):245]. J Am Dent Assoc.2019;150(4S):S32-S37.

13. Seriwatanachai D, Triratana T, Kraivaphan P, et al. Effect of stannous fluoride and zinc phosphate dentifrice on dental plaque and gingivitis: a randomized clinical trial with 6-month follow-up. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150(4S):S25-S31.

14. Hines D, Xu S, Stranick M, et al. Effect of a stannous fluoride toothpaste on dentinal hypersensitivity: in vitro and clinical evaluation. J Am Dent Assoc. 2019;150(4S):S47-S59.

15. Makin SA. Stannous fluoride dentifrices. Am J Dent. 2013;26(spec no A):3A-9A.

16. Rosier BT, De Jager M, Zaura E, Krom BP. Historical and contemporary hypotheses on the development of oral diseases: are we there yet? Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2014;4:92.

17. Zhang S, Govindaraju GV, Cheng CY, et al. Oxidative stability of chelated Sn(II)(aq) at neutral pH: the critical role of NO3− ions. Sci Adv. 2024;10(40). doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adq0839.

18. Elias-Boneta AR, Mateo LR, D'Ambrogio R, et al. Efficacy of a novel stannous fluoride toothpaste stabilized with nitrate and phosphates (SNaP) in extrinsic tooth stain removal: a randomized controlled trial. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2024;45 suppl 3:46-52.

19. Cabelly A, Bankova M, Darling J, et al. Stannous fluoride toothpaste stabilized with nitrate and phosphates (SNaP) reduces oral malodor: a randomized clinical study. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2024;45 suppl 3:40-45.

20. Liu Y, Lavender S, Ayad F, et al. Effect of a stannous fluoride toothpaste stabilized with nitrate and phosphates (SNaP) on dentin hypersensitivity: in vitro study and randomized controlled trial. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2024;45 suppl 3:30-39.

21. Hu D, Zhang YP, Petrone M, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a triclosan/copolymer/sodium-fluoride dentifrice in controlling oral malodor: a three-week clinical trial. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2003;24(9 suppl):34-41.

22. Löe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21(6):533-551.

23. Turesky S, Gilmore ND, Glickman I. Reduced plaque formation by the chloromethyl analogue of victamine C. J Periodontol.1970;41(1):41-43.

24. Ferreira MC, Dias-Pereira AC, Branco-de-Almeida LS, et al. Impact of periodontal disease on quality of life: a systematic review. J Periodontal Res.2017;52(4):651-665.

25. Broomhead T, Gibson B, Parkinson CR, et al. Gum health and quality of life-subjective experiences from across the gum health-disease continuum in adults. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22(1):512.

26. Romito GA, Feres M, Gamonal J, et al. Periodontal disease and its impact on general health in Latin America: LAOHA Consensus Meeting Report. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34(supp1 1):e027.