Opioid abuse and misuse remain a significant problem for dental and medical professionals.

One need only review a 2011 article in the Journal of the American Dental Association to appreciate the persistent and broad impact of opioid-related problems on the dental profession, as well as on patients, their families, and society at large.1 According to the authors of the article, 5% to 23% of all prescribed opioid doses are used nonmedically, with immediate-release (IR) opioids—i.e., hydrocodone and oxycodone—being the most problematic.1,2 Significantly, dentists prescribe 12% of all IR opioids in the United States, second only to family physicians, who prescribe 15% of IR opioids.3 Prescribing opioids is particularly prevalent following third-molar removal—especially among oral and maxillofacial surgeons, who expose approximately 3.5 million people annually to opioids in the United States.4

In examining the problems of opioid misuse, abuse, diversion, and addiction, the authors of the above-mentioned article reviewed the American Dental Association’s position on the use of opioids for the treatment of dental pain5 (Figure 1). In this statement, continuing education on proper opioid prescribing patterns, beginning in dental school curricula and continuing throughout practitioners’ practice lifetimes, is encouraged. The authors also point out that many state dental licensing boards have developed advisory statements regarding pain management in dentistry, placing the onus of responsibility for proper prescribing patterns on the individual practitioner.

An additional review of opioid prescribing patterns in dentistry by Oakley et al examines the rise in prescription drug abuse in the United States in an effort to alert the dental community of its responsibility to help prevent the misuse and abuse of prescription drugs.6 According to the authors, nonmedical use of prescription drugs occurs among 7 million Americans per month, surpassing the number of Americans abusing heroin, cocaine, hallucinogens, and inhalants combined.6,7 Opioid analgesics such as Percodan® (Endo Pharmaceuticals, www.endo.com) and Vicodin® (Abbott Laboratories, www.abbott.com) in particular are the most frequently abused of prescription drugs and are some of the most frequently prescribed drugs in the United States in both medicine and dentistry8 (Table 1). Given the magnitude of nonmedical use of opioid prescriptions, according to Oakley et al, it is incumbent upon dentists to keep abreast of current trends in prescription drug abuse and to undertake prudent precautions when prescribing opioid analgesics for postoperative dental pain6 (Table 2).

Additional Problems Related to Postoperative Opioid Use

Although opioid misuse and abuse are significant societal problems, complications and side effects related to opioids—i.e., nausea, vomiting, and potential for respiratory depression—pose difficult postoperative challenges for clinicians. Other potential opioid-induced side effects include the following:

Opioid-Induced Sedation—Opioid-induced sedation and drowsiness are well known side effects of opioids and are thought to be caused by the anticholinergic activity of opioids.9,10 Although tolerance to these side effects often develops with long-term use, short-term use for acute postoperative pain often leads to sedation, limiting patient quality of life.6

Opioid-Induced Sleep Disturbances—Although less well known, opioids, which alter the balance of neurotransmitters regulating wake/sleep patterns—i.e., noradrenaline, serotonin, acetylcholine, dopamine, and others—can potentially affect sleep.9 Although the exact mechanisms by which opioids disrupt sleep is unclear, morphine, for example, may reduce REM sleep in part by inhibiting acetylcholine release in the medial pontine reticular formation of the brain.11

Opioid-Induced Constipation—Constipation is a common side effect, occurring in 40% to 95% of patients treated with opioids and can occur with a single dose of morphine.12,13 Opioid-induced constipation can result in significant morbidity, and if severe enough, mortality. Severe constipation can result in forced reduction of the prescribed opioid dose, leading to inadequate analgesia. More significantly, chronic constipation can lead to rectal pain, hemorrhoid formation, bowel obstruction, and possible bowel rupture and death. Unlike other opioid-related side effects—i.e., nausea, sedation, and respiratory depression—constipation is unlikely to improve with time.14

Opioid-Induced Bladder Dysfunction—Bladder dysfunction—i.e., difficulty voiding or urinary retention—occurs in 4% to 18% of patients receiving postoperative opioid medication.15,16 Opioids decrease detrusor muscle tone and the force of bladder contraction, decrease the sensation of bladder fullness and the urge to void, and inhibit the voiding reflex. Both opioid-mediated central effects on the brain and spinal cord and peripheral effects at the bladder contribute to urinary dysfunction.

In general, the most common opioid-induced complications are nausea and constipation, followed by sedation/drowsiness, and vomiting. Of all known complications, respiratory depression and death from opioid overdose are the most feared. However, in the acute postoperative period following dental surgical procedures, in the presence of careful patient instruction and close clinician monitoring, respiratory depression and death are unlikely.

Current Alternatives to Immediate-Release Opioids in Dental Practice

While opioids are commonly prescribed following dental, periodontal, and oral surgical procedures, there are alternative strategies for acute pain management that may avoid opioid-related complications. In the immediate postoperative period, administering a long-acting local anesthetic, such as bupivacaine, may delay the onset of acute pain, allowing adequate absorption time for an orally prescribed analgesic to take effect.17,18 Prophylactically administering second-generation nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen 400 to 600 mg or naproxen 50 mg, or combining NSAID analgesics with N-acetyl-p-aminophenol (APAP/acetaminophen) immediately prior to surgery, may diminish felt pain intensity during the immediate postoperative period, especially in the presence of mild to moderate pain.19,20 Continued use of these same NSAIDs during the next 2 to 5 days may be sufficient to control postsurgical pain and discomfort, especially in mild to moderate degrees of discomfort or pain. Intravenous glucocorticoids given at the end of surgery may also be considered in selected instances when excessive swelling is likely to occur following a dental surgical procedure.21

SPRIX® (ketorolac tromethamine) Nasal Spray: An Alternative to Opioids

Although generally effective in diminishing acute postoperative pain, the significant side effects of opioids, along with their potential for misuse, abuse, and addiction, have prompted the need for a new nonopioid analgesic alternative equipotent to opioids in both medicine and dentistry. SPRIX® (Regency Therapeutics, Division of Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc., www.sprix.com) is an intranasal (IN) formulation of ketorolac tromethamine (ketorolac), a nonopioid NSAID with potent analgesic effects recently approved for the short-term (up to 5 days) management of moderate to moderately severe pain requiring analgesia at the opioid level.

What is Ketorolac?

Ketorolac, like other NSAIDs, produces its therapeutic activities through inhibition of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, the enzymes that metabolize arachidonic acid to prostaglandins, prostacyclin, and thromboxane. When prostaglandins are released from injured tissues, they increase the sensitization of afferent nerve endings that originate at sites of injury and inflammation. NSAIDs decrease the hyperalgesic sensitivity of these nerve endings, and thus diminish pain. All NSAIDs share analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic activities, but each agent has its own efficacy and safety profile; some NSAIDs have predominantly analgesic activity, while others have stronger anti-inflammatory effects.

Parenteral Ketorolac

Parenteral ketorolac has been used in the United States since 1990, primarily in the hospital setting, as an effective alternative to opioids or concomitantly with opioids as part of a multimodal “balanced analgesia” regimen. In clinical use as an alternative to opioids, ketorolac has proven to provide effective analgesia without the side effects associated with opioids, such as constipation,

CNS effects, or respiratory depression. In addition, ketorolac provides an important alternative for pain control in situations in which a physician is uncomfortable prescribing opioids, as in patients with a history of substance abuse.

Experience with intramuscular (IM) ketorolac has shown it to be an effective analgesic for short-term (5 days or less) treatment of moderate-to-severe postoperative pain, with potency similar to that of 6 mg to 12 mg of morphine22 or 50 mg to 100 mg of meperidine; it has also confirmed its utility in other acute pain states, such as renal colic, posttraumatic musculoskeletal pain, visceral pain associated with cancer, and pain associated with abdominal, gynecologic, oral, orthopedic, and urologic surgery.23 The marked analgesic efficacy of ketorolac in humans raised questions about whether ketorolac is an especially potent COX inhibitor or if it has additional, non-COX activities. Studies showed that, although ketorolac is a potent inhibitor of both COX-1 and COX-2, its anti-COX activity is similar to that of indomethacin or diclofenac sodium; therefore COX activity alone does not account for its analgesic strength.

Additional research has focused on how the pharmacology and physiochemical properties of ketorolac tromethamine might contribute to its potency. Ketorolac is 100% bioavailable when administered intramuscularly. Although it is lipophilic, allowing it to cross lipid bilayer cell membranes, it is less lipophilic than other NSAIDs, such as indomethacin and diclofenac, resulting in less deposition into body fat stores. In addition, ketorolac tends not to be distributed well beyond the vascular compartment.24,25 The net result of these unique properties limits ketorolac’s diffusion and optimizes its concentration at sites of tissue damage and COX enzyme release, resulting in higher local tissue concentrations (e.g., around third-molar extraction sites) than would be predicted by systemic blood levels and resulting in greater efficacy and potency when used for acute postoperative pain.26

The clinical trials that were conducted to examine all aspects of parenteral ketorolac established that IM ketorolac was an effective NSAID analgesic with a suitable risk/benefit profile for the treatment of acute pain. Dose-ranging studies conducted during these trials established that IM doses of 15 mg to 30 mg of ketorolac every 6 to 8 hours were safe and effective for short-term (up to 5 days) analgesic use. Post-marketing clinical experience with IM ketorolac in both inpatients and outpatients confirmed the safety and efficacy of IM ketorolac as an effective alternative to opioids.

SPRIX® (ketorolac tromethamine) Nasal Spray: An Alternative to Opioids for the Management of Acute Postoperative Dental Pain

Currently there are no nonopioid alternatives for the treatment of moderate to severe pain other than ketorolac. The question arose whether an alternative formulation of IM ketorolac could be designed that would be equally safe and effective for treating acute pain in outpatient settings.

Ketorolac tromethamine has a unique solubility profile that allows it to be formulated as a nasal spray. SPRIX® provides blood levels of ketorolac in the range between those obtained with the two doses of IM ketorolac (15 mg and 30 mg) that are approved for repeated administration (Table 3).

As noted in Table 3, the half-life and absorption kinetics of SPRIX® are similar to that of IM ketorolac.

SPRIX® Development Program

The objectives of the SPRIX® development program were to find an intranasal (IN) formulation that provided reproducible blood levels of ketorolac in a range similar to that of the IM formulation, which was known to provide adequate analgesia, and to develop a formulation that was well tolerated with minimal side effects.

The development program conducted by ROXRO PHARMA, Inc. (ROXRO, Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc., www.luitpold.comluitpold.com) for an intranasal (IN) formulation of ketorolac tromethamine (hereafter referred to as ketorolac) included a total of 14 clinical studies conducted by the sponsor, in which over 1,000 subjects participated, with almost 750 receiving the active entity. Four of these studies were placebo-controlled Phase 2 or Phase 3 efficacy studies in which patients who had undergone major surgery or dental surgery were treated for acute moderate-to-severe pain, and 10 were Phase 1 studies in healthy volunteers.

The primary objectives of the development program were:

- to establish the efficacy of SPRIX® in patients with moderate to moderately severe pain.

- to define an effective dose that also provides a satisfactory safety profile.

- to gather efficacy data with and without concomitant opioid use in patient populations including those immediately after: oral surgery; abdominal surgery; gynecological surgery; or orthopedic surgery.

- to explore the safety and efficacy of dosing frequency of every 6 hours and every 8 hours.

- to generate a safety database with safety evaluations up to 5 days.

Intranasal Ketorolac for Pain Secondary to Third-Molar Impaction Surgery: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial27

Of the four efficacy trials, one focused on the effectiveness of SPRIX® in the management of postoperative pain following third-molar impaction surgery. In this study, at least one third molar was either a partial or full-bony impacted tooth. The study consisted of 80 patients, 40 receiving a single 31.5-mg dose of SPRIX® and 40 receiving an identically administered intranasal placebo in a randomized, double-blind fashion when their pain intensity rating following a dental extraction procedure equaled at least 50-mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS), where 0 = no pain and 100 = the worst pain imaginable. The patients had access to rescue analgesic medication (acetaminophen with hydrocodone bitartrate) starting at the time of the first dose of the study drug and continuing for 8 hours after surgery, but patients were encouraged to wait at least 90 minutes after receiving the study drug before taking rescue medication.

Throughout the study, the single IN ketorolac (SPRIX®) dose was well tolerated. Eight patients in the placebo group and three in the SPRIX® group had mild adverse events. The three events in the SPRIX® group were reports of minor headache.

SPRIX® provided pain relief that was significantly better than placebo for all measures evaluated, including onset of relief (as measured by time to both perceptible and meaningful relief), peak relief (as measured by both maximum pain intensity difference [PID] and maximum relief scores at 20 and 60 minutes), and duration of analgesic effect. The evaluation of the duration of analgesic effects, as measured by the time to use of rescue medication, showed that approximately 80% of the placebo group had remedicated near hour 2, whereas about 50% of the SPRIX® group had remedicated near hour 6, and no additional patient remedicated by hour 8. The investigators concluded that the single 31.5-mg dose of intranasal SPRIX® was well tolerated and provided rapid and effective pain relief following third-molar removal surgery for a period of up to 8 hours with minimal side effects.

Overall Results of the Four SPRIX® Randomized Controlled Trials in Oral Surgery, Abdominal Surgery, Gynecological Surgery, and Orthopedic Surgery

As a result of the prospective trials examining the safety and efficacy of SPRIX®, the following findings were confirmed:

- SPRIX® provided an analgesic benefit in postoperative pain similar to that seen in previous clinical studies of IM ketorolac following major surgical procedures. Specifically, SPRIX® was found to be an effective analgesic after third-molar extraction surgery and following major abdominal, gynecologic, and orthopedic surgery.

- SPRIX® in an intranasal spray formulation provided blood levels of ketorolac and clinical efficacy similar to those obtained with IM injections of ketorolac.

- SPRIX® was effective in the adults studied (pediatric subjects were excluded) regardless of patient age, sex, or ethnicity.

- Following major surgery, when supplemental morphine sulfate was allowed in combination with intranasal SPRIX®, significantly less morphine sulfate was required to achieve satisfactory pain relief than with morphine sulfate alone.

- SPRIX® was effective in managing acute pain when administered at 6-hour or 8-hour intervals for up to 5 days and was well tolerated with either regimen.

Following review of the results of these and other trials in the SPRIX® clinical trial program, SPRIX® was approved by the FDA for the short-term (up to 5 days) management of moderate to moderately severe pain requiring analgesia at the opioid level.

An Overview Examination of SPRIX®

Formulated as an intranasal spray, SPRIX® avoids the need for IM injections or intravenous access. SPRIX® also avoids the oral route, benefiting patients who are nauseated or are unable to take oral medications. Importantly, SPRIX® offers dentists, physicians, and patients a highly needed, nonopioid option for short-term control of moderate to moderately severe pain.

Important Characteristics of SPRIX®

Clearance of SPRIX® from the nasal cavity without deposition in the lungs—Based on a scintigraphic study with radiolabeled SPRIX®, clearance of SPRIX® from the nasal cavity is initially rapid, with only 16% to 30% of the dose retained in the nasal cavity by 10 minutes post-dose. At 6 hours 9% to 14% of the dose was retained and the remainder eliminated over time. Importantly, virtually the entire dose of SPRIX® was deposited in the nasal cavity, with zero or negligible deposition in the lungs.

Lack of sedation secondary to lack of CNS activity — SPRIX® has no sedative activity. Although NSAIDs such as SPRIX® may have some minor central nervous system activity, they work mainly through peripheral mechanisms of action; therefore, unlike opioids, they do not produce significant sedation, tolerance, or addiction.

SPRIX® is currently not indicated for use in children—An open-label, single-dose SPRIX® study in 20 pediatric patients age 12 to 17 who had undergone general surgery was undertaken to initially examine the feasibility of prescribing SPRIX® in children. While the pharmacokinetic results reported in this study presented no special safety concerns, SPRIX® is currently not approved for use in pediatric patients.

SPRIX® can be prescribed for elderly patients, but at a reduced dose — The results of an open-label study that compared the pharmacokinetic and safety profiles of SPRIX® in patients > age 65 revealed that the total exposure in elderly patients was approximately 23% higher than in nonelderly adults. This study did not find any increase in adverse events for elderly patients. Based on these pharmacokinetic findings, the prescribing information for SPRIX® calls for a reduced dose of 15.75 mg (one spray only) every 6 to 8 hours for patients > 65 years of age.

Potential Side Effects, Complications, and Drug Interactions with SPRIX®

All drugs, no matter how benign, have potential side effects, complications, and possible interactions with other medications. SPRIX®, with a wide margin of safety, is no exception. The following is a brief review of the most common adverse events, complications, and drug interactions associated with SPRIX®. For a complete review, clinicians should consult “important safety information” (ISI), including the boxed warning (see end of article).

Potential Common Adverse Events Related to SPRIX®

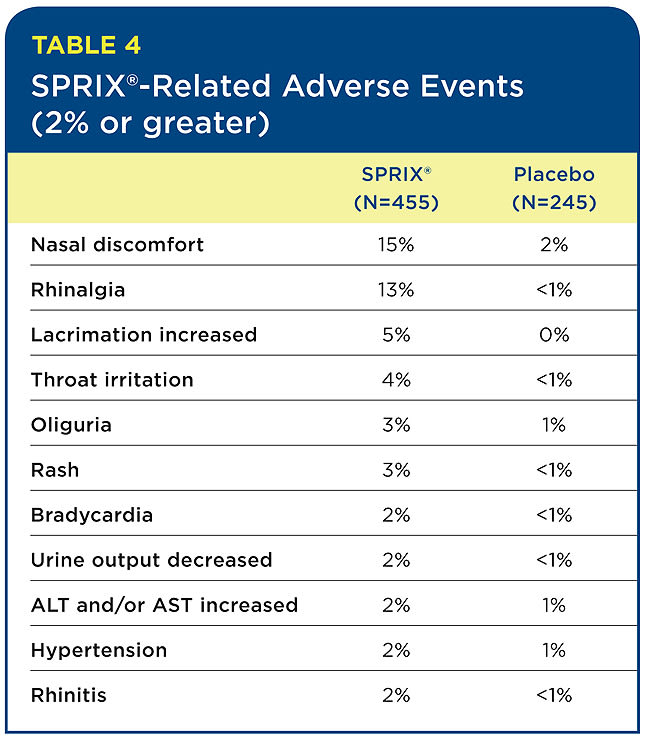

The most common adverse events that appear to be related to SPRIX® are local events, such as nasal discomfort, rhinalgia (nasal stinging), increased lacrimation, and throat irritation. Nasal adverse events aggregated from the various SPRIX® clinical trials were transient. Interestingly, in the oral surgery third-molar study, the only adverse events reported in the SPRIX® group (three patients out of 40) were mild headaches, with no nasal or other events evident.

Table 4 lists the percentage of SPRIX®-related adverse reactions observed at a rate of 2% or more and at least twice the incidence of the placebo group. (SPRIX® group = 455 patients; placebo group = 245 patients). In these same controlled clinical trials, seven patients (N=455, 1.5%) treated with SPRIX® experienced serious adverse events of bleeding (four patients) or hematoma (three patients) at the operative site versus one patient (N=245, 0.4%) treated with placebo (hematoma). Six of the seven patients treated with SPRIX® underwent a surgical procedure and/or blood transfusion, and the placebo patient subsequently required a blood transfusion.

Oliguria and decreased urine output, when evaluated by the study investigators, were in general not thought to be related to SPRIX®. However, oliguria and decreased urine output can occur with NSAIDs, including ketorolac. Hypertension, bradycardia, and rash were likewise considered unrelated to SPRIX® administration. However, because these events occurred at two times the rate in the placebo group, they were included in Table 4.

The events often seen with long-term use of NSAIDs—including peptic ulcer disease with perforation, ulceration, and bleeding—were not seen in these short-term studies and should be uncommon when SPRIX® is used per label with dosing limited to 5 days.

Concomitant Use of Other Medications and Potential Drug Interactions with SPRIX®

Concomitant Administration of SPRIX® With Other Common Intranasal Medications

Oxymetazoline hydrochloride (available in the U.S. as AFRIN® [www.afrin.com] and other brands) nasal spray is a widely used nonprescription decongestant used to reduce congestion associated with allergies, hay fever, sinus irritation, and the common cold. It is used on an intermittent, short-term, as needed basis. A prospective study was conducted in healthy male volunteers to evaluate whether the absorption of SPRIX® would change with co-administration of oxymetazoline. SPRIX® was administered 30 minutes after a single dose of oxymetazoline (3 sprays of a 0.05% solution into each nostril). The administration of oxymetazoline nasal spray 30 minutes prior to dosing with SPRIX® did not have an effect of clinical significance on either the rate or the extent of ketorolac absorption.

Fluticasone propionate (available in the U.S. as Flonase® [GlaxoSmithKline USA, https://us.gsk.com]) nasal spray is a popular prescription formulation of IN corticosteroid. Chronic use of steroid nasal sprays may result in atrophic changes of the nasal mucosa, which may have an effect on the absorption and tolerability of other drugs administered IN. An open-label study in healthy volunteers was conducted in which SPRIX® was administered before and after 5 days of once-daily IN administration of 200 mcg of fluticasone. The administration of fluticasone propionate for 5 days did not have an effect of clinical significance on either the rate or the extent of ketorolac absorption.

In addition, subjects with symptomatic allergic rhinitis received a single dose of oxymetazoline nasal spray followed by a single dose (31.5 mg) of SPRIX® 30 minutes later. Subjects also received fluticasone nasal spray (200 mcg as 2 x 50 mcg in each nostril) for 7 days, with a single dose (31.5 mg) of SPRIX® on the 7th day. Administration of these common IN products had no effect of clinical significance on the rate or extent of ketorolac absorption. In addition, comparison of the pharmacokinetics of SPRIX® in subjects with allergic rhinitis to data from a previous study in healthy subjects showed no differences that would be of clinical consequence for the efficacy or safety of SPRIX®.

Concomitant Administration of SPRIX® with Other Medications and Potential Drug Interactions

Ketorolac is highly bound to human plasma protein (mean 99.2%). There is no evidence in animal or human studies that ketorolac tromethamine induces or inhibits hepatic enzymes capable of metabolizing itself or other drugs. Therapeutic concentrations of digoxin (Lanoxin® [GlaxoSmithKline USA)]), warfarin (Coumadin® [Bristol-Myers Squibb, www.coumadin.com]), ibuprofen (Advil® [Pfizer, Inc., www.advil.com], Addaprin® [Dover Medique Products, www.mediqueproducts.com], Dolgesic [FerrerGrupo Pharmaceuticals, www.ferrergrupo.com]), naproxen (Aleve® [Bayer AG, www.aleve.com], Anaprox® [Roche Pharmaceuticals, www.roche.com], Midol® [Bayer AG, www.midol.com]), piroxicam (Feldene® [Pfizer, www.pfizer.com]), acetaminophen (Tylenol® [www.tylenol.com], etc.), phenytoin (Dilantin® [Pfizer]) and tolbutamide did not alter ketorolac protein binding.

No new adverse drug interactions were noted in the SPRIX® clinical studies, but the following drug interactions noted for injectable ketorolac (Ketorolac IM/IV Label, 2008) may be important for SPRIX®:

- SPRIX® should not be used concomitantly with IM, IV, or oral formulations of ketorolac. If used sequentially, the combined use of SPRIX® and other ketorolac formulations should not exceed 5 days for any pain episode.

- ACE-inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor antagonists—Concomitant use of ACE inhibitors and/or angiotensin II receptor antagonists may increase the risk of renal impairment, particularly in volume-depleted patients. NSAIDs such as SPRIX® may diminish the antihypertensive effect of ACE-inhibitors and/or angiotensin II receptor antagonists.

- Anticoagulants—The effects of anticoagulants, such as warfarin, taken concomitantly with NSAIDs, such as SPRIX®, on gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding are synergistic. Combined use may increase the risk of serious GI bleeding. Although studies do not indicate a significant interaction between ketorolac and warfarin or heparin, extreme caution should be exercised in the administration of ketorolac to patients taking anticoagulants, and the patients should be closely monitored.

- Anti-epileptic drugs—Sporadic cases of seizures have been reported during concomitant use of ketorolac and antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin, carbamazepine).

- Aspirin—When ketorolac is administered with aspirin, the protein binding of ketorolac is reduced, although the clearance of free ketorolac is not altered. Concomitant administration of SPRIX® and aspirin is not generally recommended because of the potential of increased adverse effects. In vitro studies indicate that, at therapeutic concentrations of salicylate (300 mcg/mL), the binding of ketorolac was reduced from approximately 99.2% to 97.5%, representing a potential twofold increase in unbound ketorolac plasma levels.>

- Cyclosporine—NSAIDs such as SPRIX® may affect renal prostaglandins and increase the nephrotoxicity of cyclosporine.

- Digoxin—Ketorolac does not alter digoxin protein binding.

- Diuretics—NSAIDs such as SPRIX® can reduce the natriuretic effect of furosemide (Lasix® [Sanofi-Aventis, www.sanofi.us]) and thiazides in some patients through inhibition of renal prostaglandin synthesis.

- Lithium—NSAIDs have produced an elevation of plasma lithium levels and a reduction in renal lithium clearance, effects which have been attributed to inhibition of renal prostaglandin synthesis by the NSAID. If SPRIX® and lithium are administered concurrently, subjects should be observed carefully for signs of lithium toxicity.

- Methotrexate—NSAIDs may enhance the toxicity of methotrexate. Caution should be used when NSAIDs are administered concomitantly with methotrexate.

- Morphine—SPRIX® has been administered concurrently with morphine in multiple clinical trials of postoperative pain. Each of these studies indicates that SPRIX® has an opioid-sparing effect, i.e., less morphine is needed when used in combination with SPRIX®.

- Nondepolarizing muscle relaxants—In postmarketing experience with ketorolac IM/IV there have been reports of a possible interaction between ketorolac IV/IM and nondepolarizing muscle relaxants that resulted in apnea.

- NSAIDs—Concomitant use of other NSAIDs may increase adverse NSAID effects of SPRIX®.

- Pentoxifylline (Trental® [Sanofi-Aventis U.S. LLC, www.sanofi.us], Pentoxil® [Upsher-Smith, www.upsher-smith.com], Flexital® [Sun Pharmaceutical, www.sunpharma.com])—When ketorolac is administered concurrently with pentoxifylline, there is an increased tendency for bleeding.

- Probenecid—No studies have been conducted with the concomitant administration of probenecid and SPRIX®. However, concomitant administration of probenecid and ketorolac resulted in decreased clearance and volume of distribution of ketorolac and significant increases in ketorolac plasma levels. SPRIX® and probenecid should not be taken concomitantly, as the plasma levels of ketorolac may be increased, increasing the risk that adverse events may occur.

- Psychoactive drugs—Hallucinations have been reported when ketorolac was used in patients taking psychoactive drugs (fluoxetine (Prozac® [Eli Lilly, www.prozac.com], thiothixene (Navane® [Pfizer]), alprazolam (Xanax® [Pfizer], Niravam® [Edgemont Pharmaceuticals, Inc., www.edgemontpharma.com]).

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—There is an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding when SSRIs are combined with NSAIDs.

Summary

In summary, SPRIX® is a nonopioid alternative for the management of moderate to moderately severe pain.

- SPRIX® offers dentists, physicians, and patients a new nonopioid option to control acute moderate to moderately severe pain in situations in which use of an IM or IV access is not feasible or not wanted.

- SPRIX® is a valuable treatment option for patients with nausea or vomiting, those unable to take oral medications, and those unable to tolerate the side effects of opioids.

- In ambulatory acute pain settings, use of SPRIX® will allow patients who need to remain alert to receive effective pain control. Currently, there are no nonopioid alternatives for the treatment of moderate to moderately severe pain other than ketorolac.

- In patients with more severe pain states, the combination of opioids and SPRIX® provides unique advantages in maximizing analgesia while minimizing the unwanted adverse effects of both classes of drugs (referred to as multimodal or “balanced analgesia”).

Disclosure

The authors are employees of Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the marketer of SPRIX® Nasal Spray.

About the Authors

Mark B. Snyder, DMD

Clinical Associate Professor

Department of Periodontics

University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Medical Director

Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Norristown, Pennsylvania

David B. Bregman, MD, PhD

Associate Clinical Professor

Department of Pathology

Albert Einstein College of Medicine

New York, New York

Medical Director

Luitpold Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Norristown, Pennsylvania

Important Prescribing Information

Each vial of SPRIX® provides 24 hours of medication (8 sprays). SPRIX® can be prescribed for up to 5 days as needed. Do not exceed a total combined duration of SPRIX® and other ketorolac formulations (IM/IV or oral) of 5 days.

Before using SPRIX®, patients must activate or prime the pump by spraying it five times with the nozzle pointed away from them. Patients should blow their nose gently to clear their nostrils. While tilting their head forward, they should insert the nozzle pointing away from the midline. The patient should press down evenly on the pump to deliver one spray. This step should be repeated in the other nostril if prescribing 31.5 mg.

It is not necessary to inhale SPRIX® as it is absorbed through the nasal mucosa. Advise patients that they may experience mild to moderate nasal irritation or discomfort upon dosing but that it is transient.

SPRIX® should be refrigerated in an upright position before use. After first use, the bottle can be kept at room temperature and discarded after 24 hours.

If the top portion of the nasal spray is pulled off the glass vial, patients can reinsert it by lining up the nozzle and softly pushing it back into position.

How to Prescribe SPRIX® (ketorolac tromethamine) Nasal Spray

For adult patients < 65 years of age:

- 31.5 mg (one 15.75 mg spray in each nostril) every 6 to 8 hours.

- The maximum daily dose is 126 mg.

For patients ≥ 65 years of age, renally impaired patients, and patients < 50 kg (110 lbs.):

- 15.75 mg (one 15.75 mg spray in only one nostril) every 6 to 8 hours.

- The maximum daily dose is 63 mg.

IMPORTANT SAFETY INFORMATION

WARNING: LIMITATIONS OF USE, GASTROINTESTINAL, BLEEDING, CARDIOVASCULAR, and RENAL RISK

Limitations of Use—SPRIX® (ketorolac tromethamine) Nasal Spray, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), is indicated for short-term (up to 5 days in adults) management of moderate to moderately severe pain that requires analgesia at the opioid level. Do not exceed a total combined duration of use of SPRIX® and other ketorolac formulations (IM/IV or oral) of 5 days.

SPRIX® is not indicated for use in pediatric patients and it is not indicated for minor or chronic painful conditions.

Gastrointestinal Risk—Ketorolac tromethamine, including SPRIX®, can cause peptic ulcers, gastrointestinal bleeding and/or perforation of the stomach or intestines, which can be fatal. These events can occur at any time during use and without warning symptoms. Therefore, SPRIX® is contraindicated in patients with active peptic ulcer disease, in patients with recent gastrointestinal bleeding or perforation, and in patients with a history of peptic ulcer disease or gastrointestinal bleeding. Elderly patients are at greater risk for serious gastrointestinal events.

Bleeding Risk—Ketorolac tromethamine inhibits platelet function and is, therefore, contraindicated in patients with suspected or confirmed cerebrovascular bleeding, patients with hemorrhagic diathesis, incomplete hemostasis and those at high risk of bleeding.

Cardiovascular Risk—NSAIDs may cause an increased risk of serious cardiovascular thrombotic events, myocardial infarction, and stroke, which can be fatal. This risk may increase with duration of use. Patients with cardiovascular disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease may be at greater risk.

SPRIX® is contraindicated for treatment of perioperative pain in the setting of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.

Renal Risk—SPRIX® is contraindicated in patients with advanced renal impairment and in patients at risk for renal failure due to volume depletion.

SPRIX® is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity or history of asthma, urticaria, or other allergic-type reactions to aspirin, ketorolac, other NSAIDs or EDTA. However, anaphylactoid reactions may occur in patients with or without a history of allergic reactions to aspirin or NSAIDs. SPRIX® is contraindicated in patients as a prophylactic analgesic prior to major surgery; or in labor, delivery, or nursing mothers because of the potential adverse effects of prostaglandin-inhibiting drugs on neonates.

SPRIX® should not be used concomitantly with IM/IV or oral ketorolac, aspirin, or other NSAIDs, or with probenecid or pentoxifylline. When ketorolac is administered with aspirin, its protein binding is reduced, although the clearance of free ketorolac is not altered. The clinical significance of this interaction is not known; however, as with other NSAIDs, concomitant administration of SPRIX® and aspirin is not generally recommended because of the potential of increased adverse effects.

Do not use SPRIX® in patients for whom hemostasis is critical.

Clinical studies, as well as postmarketing observations, have shown that ketorolac can reduce the natriuretic effect of furosemide and thiazides in some patients.

Concomitant use of ACE inhibitors and/or angiotensin II receptor antagonists may increase the risk of renal impairment, particularly in volume-depleted patients. NSAIDs may diminish the antihypertensive effect of ACE inhibitors and/or angiotensin II receptor antagonists. Consider this interaction in patients taking SPRIX® concomitantly with ACE inhibitors and/or angiotensin II receptor antagonists.

Ketorolac can cause serious GI adverse events including bleeding, ulceration, and perforation. Elderly patients are at increased risk for serious GI events.

Use SPRIX® with caution in patients with impaired hepatic function or a history of liver disease.

The pharmacologic activity of SPRIX® in reducing inflammation and fever may diminish the utility of these diagnostic signs in detecting infections.

Avoid contact of SPRIX® with the eyes. If eye contact occurs, wash out the eye with water or saline, and consult a physician if irritation persists for more than an hour.

Ketorolac can cause renal injury. SPRIX® Nasal Spray should be used with caution in patients with advanced renal disease or patients at risk for renal failure due to volume depletion and should be used with caution in patients taking diuretics or ACE inhibitors. Long-term administration of NSAIDs has resulted in renal papillary necrosis and other renal injury such as interstitial nephritis and nephrotic syndrome.

NSAIDs can cause serious dermatologic adverse reactions such as exfoliative dermatitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and toxic epidermal necrolysis, which can be fatal. These serious events may occur without warning. SPRIX® should be discontinued immediately in patients with skin reactions.

During pregnancy, use of SPRIX® beyond 30 weeks’ gestation can cause premature closure of the ductusarteriosus, resulting in fetal harm (Pregnancy Category D). Prior to 30 weeks’ gestation, SPRIX® should be used during pregnancy only if potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus (Pregnancy Category C).

NSAIDs can lead to onset of new hypertension or worsening of preexisting hypertension, either of which may contribute to the increased incidence of cardiovascular events. Patients taking thiazides or loop diuretics may have impaired response to these therapies when taking NSAIDs. Fluid retention, edema, retention of NaCI, oliguria, and elevations of serum urea nitrogen and creatinine have been reported in clinical trials with ketorolac. Only use SPRIX® very cautiously in patients with cardiac decompensation or similar conditions.

The most common adverse reactions (incidence > 2%) in patients treated with SPRIX® and occurring at a rate at least twice that of placebo are nasal discomfort, rhinalgia, increased lacrimation, throat irritation, oliguria, rash, bradycardia, decreased urine output, increased ALT and/or AST, hypertension, and rhinitis.

Treat patients for the shortest duration possible, and do not exceed 5 days of therapy with SPRIX®.

For complete Prescribing Information, including Boxed Warning, please call 1-888-354-4855 or visit www.sprix.com.

References

1. Denisco RC, Kenna GA, O’Neil MF, et al. Prevention of prescription opioid abuse: The role of the dentist. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(7):800-810.

2. Katz NP, Birnbaum HG, Castor A. volume of prescription opioids used nonmedically in the United States. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2010; 24(2):141-144.

3. Rigoni GC. Drug Utilization for Immediate- and Modified Release Opioids in the US. Silver Spring, MD: Division of Surveillance, Research & Communication Support, Office of Drug Safety, Food and Drug Administration; 2003. www.fda.gov/ohrms/DOCKETS/AC/03/SLIDES/3978S1_05_Rigoni.ppt.

4. Moore PA, Nahouraii HS, Zovko JG, Wisniewski SR. Dental therapeutic practice patterns in the U.S., II: analgesics, corticosteroids, and antibiotics. Gen Dent. 2006;54(3):201-207.

5. American Dental Association. ADA Current Policies: Adopted 1954-2009-Substance Use Disorders, Statement on the Use of Opioids in the Treatment of Dental Pain. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2010:227.

6. Oakley M, O’Donnell J, Moore PA, Martin J. The rise in prescription drug abuse: Raising awareness in the dental community. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2010;32(6):14-24.

7. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Congressional Caucus on Prescription Drug Abuse. Available at: https://www.drugabuse.gov/Testimony/9-22-10Testimony.html. Accessed December 28, 2011.

8. National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA Info-Facts Drug-Related Hospital Emergency Room Visits. Available at: https://www.drugabuse.gov/infofacts/HospitalVisits.html. Accessed December 28, 2011.

9. Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician. 2008;11(2 Suppl):S105-S120.

10. Byas-Smith MG, Chapman SL, Reed B, Cotsonis G. The effect of opioids on driving and psychomotor performance in patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2005(4);21:345-352.

11. Slatkin N, Rhiner M. Treatment of opioid-induced delirium with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: A case report. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004; 27(3):268-273.

12. Yuan CS, Foss JF. Antagonism of gastrointestinal opioid effects. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2000;25(6):639-642.

13. Sternini C. Receptors and transmission in the brain-gut axis: Potential for novel therapies. III. Mu-opioid receptors in the enteric nervous system. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281(1):G8-15.

14. Schug SA, Garrett WR, Gillespie G. Opioid and non-opioid analgesics. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2003;17(1):91-110.

15. Tammela T, Kontturi M, Lukkarinen O. Postoperative urinary retention. I. Incidence and predisposing factors. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1986;20(3):197-201.

16. O’Riordan JA, Hopkins PM, Ravenscroft A, Stevens JD. Patient-controlled analgesia and urinary retention following lower limb joint replacement: A prospective audit and logistic regression analysis. Eur J Anesthesiol. 2000;17(7):431-435.

17. Gordon SM, Mischenko AV, Dionne RA. Long-acting local anesthetics for perioperative pain management. Dent Clin North Am. 2010;54(4):611-620.

18. Moore PA. Bupivacaine: a long-lasting local anesthetic for dentistry. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58(4):369-374.

19. Barden J, Edwards JE, McQuay HJ, et al. Relative efficacy of oral analgesics after third molar extraction. Br Dent J. 2004;197(7):407-411.

20. Ong CK, Seymour RA, Lirk P, Merry AF. Combining paracetamol (acetaminophen) with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a qualitative systematic review of analgesic efficacy for acute postoperative pain. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(4):1170-1179.

21. Moore PA, Brar P, Smiga ER, Costello BJ. Preemptive rofecoxib and dexamethasone for prevention of pain and trismus following third molar surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005 Feb;99(2):E1-7.

22. Brown CR, Mazzulla JP, Mok MS, et al. Comparison of repeat doses of intramuscular ketorolac tromethamine and morphine sulfate for analgesia after major surgery. Pharmacotherapy. 1990;10(6):45S-50S.

23. Gillis JC, Brogden RN. Ketorolac. A reappraisal of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in pain management. Drugs. 1997;53(1):139-188.

24. Mroszczak EJ, Combs D, Chaplin M, et al. Chiral kinetics and dynamics of ketorolac. J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;36(6):521-539.

25. Mroszczak EJ, Lee FW, Combs D, et al. Ketorolac tromethamine absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and pharmacokinetics in animals and humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 1987;15(5):618-626.

26. Jett MF, Ramesha CS, Brown CD, et al. Characterization of the analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of ketorolac and its enantiomers in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;288(3):1288-1297.

27. Grant GM, Mehlisch DR. Intranasal ketorolac for pain secondary to third molar impaction surgery: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010; 68(5):1025-1031.