Noel Kelsch, RDHAP

The importance of the dental professional in encouraging patients to achieve good standards of oral self-care cannot be underestimated. Effectiveness in helping patients incorporate oral health-promoting behaviors, including the routine daily use of probiotics, may depend upon the dental professional’s ability to motivate patients to accept and adopt these new agents and behaviors. As dental professionals acquire a better understanding of what probiotics are and how they work, they can transfer this knowledge to patients to help them reach their health objectives.

Probiotics may be introduced as part of a medical and wellness model, which begins with the diagnosis and treatment of a condition, such as gingivitis. Adding probiotics to the treatment protocol can be the first line of defense. This therapy may prevent disease before it has occurred. It may also aid in the treatment of disease and the prevention of reoccurrence. After treatment is completed, an assessment and follow up occurs, with additional therapy if needed. Efforts to stabilize the healthier state achieved during the active treatment and to encourage further healing and resolution with probiotics may be effectively initiated to promote ongoing health.

Understanding the role of probiotics in the promotion of health, especially oral health, is very important in the development of a probiotic protocol, as one element of a comprehensive treatment plan for patient care through compliance and motivation.

Probiotic agents are becoming more widely available. The World Health Organization defines probiotics as “live microorganisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.” With their antimicrobial properties, probiotics are useful adjuncts in promoting and maintaining health. Probiotics have been shown to be effective in many body systems where the maintenance of a healthy balanced microbial ecosystem is essential: the gastrointestinal tract, the respiratory tract, the genitourinary tract, as well as the oral cavity.

Research on the efficacy and safety of probiotics for periodontal treatment is increasing; published studies have concluded that the therapeutic benefits of probiotics in oral healthcare hold promise,1-6 although more research with randomized controlled trials is needed.

Probiotic therapy adopts a wellness rather than an illness model, with the goal of healing and stabilizing the periodontal condition, using bacteria to help establish an oral health balance. Typically American medicine has focused on the illness model, treating symptoms as they arise. Shifting focus to the wellness model allows the patient to adopt measures that prevent disease from occurring and to maintain a healthy state.

Patients need to understand what probiotics are, what they do, and how they promote oral health to be able to accept the dental professional’s recommendation to initiate probiotic therapy. Patients should be made aware of the benefits of probiotic therapy. This includes knowledge of a probiotic’s ability to inhibit the growth of pathogens and encourage the proliferation of commensals, leading to a healthy and protective rather than a harmful and disease-causing dental plaque biofilm. The dental professional should explain how acidophilus and other probiotic bacteria secrete antiviral, antibacterial, and antifungal chemicals, which bind to dental surfaces and alter the conditions of the oral environment.

Dental professionals should be familiar with key features and benefits of probiotics:

Bacterial interference—one organism can either prevent or delay the growth or colonization of another member of the same or different ecosystem.

Replacement therapy—a means of offering a form of life-long protection, at a minimal cost and compliance, once the effector strain has been achieved.

Competitive displacement—when one organism displaces another organism; it is not dependent on the effector strain at or before colonization by the undesired organism.

Pre-emptive colonization—ecological niches within plaque that are filled with harmless or potentially beneficial organisms before the undesirable strain has had an opportunity to colonize or become established.

Most patients can relate to and understand an explanation of gingivitis as a bacterial infection rather than just a medical term. Dental professionals should establish treatment in terms of restoring a healthy bacterial balance, rather than merely reducing the bacterial load. Information should be shared, based on current scientific evidence on probiotics and bacterial replacement therapy, as part of a new health paradigm focused on wellness. This information must make a great enough impact to encourage compliance.

Patients need to be convinced of the effectiveness of this new type of therapy and educated on a proper protocol for obtaining the best results. Scientific studies based on Lactobacillus reuteri, the bacterial strains found in G•U•M® PerioBalance® (Sunstar Americas, Inc., www.sunstaramericas.com), have demonstrated effectiveness.5-8 The effects of probiotics are greatest when used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, which typically include directions such as:

- Perform oral hygiene regime as recommended by the dental professional.

- Take one PerioBalance probiotic lozenge per day, immediately after oral hygiene.

- Allow the PerioBalance lozenge to dissolve slowly in the mouth for at least 10 minutes.

- Do not brush teeth, floss, or use a mouthrinse after taking the product.

- Take for at least 28 days consecutively.

Two strains of Lactobacillus reuteri are the most commonly available form of oral probiotic (PerioBalance). Strain DSM 17938 produces reuterin, which is active against the putative periopathogens Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Prevotella intermedia, and Porphyromonas gingivalis. Strain ATCC PTA 5289 has the potential to block the action of TNF-alpha, an inflammatory cytokine with a pivotal action, in the development of inflammatory periodontal diseases. Lactobacillus reuteri has been shown to provide benefits not only in oral conditions such as caries, periodontal disease, and halitosis, but also in gastrointestinal and genitourinary health.

The author has achieved many successful outcomes through the incorporation of probiotics such as PerioBalance into the overall periodontal treatment protocol. Two case studies are summarized. First, a male patient with refractory periodontal disease and no instruction on plaque reduction experienced a significant decrease in plaque index, a reduction in probing depth, and cessation of severe bleeding found in most oral areas. The patient not only reported having less oral malodor, he claimed to have a lasting reversal in stomach problems of 10 years duration. The probiotic was taken daily for 28 days. At a 3-month recall, there was no further bleeding on probing, the gingival tissue was pink and firm, and the stomach symptoms had not returned (Table 1).

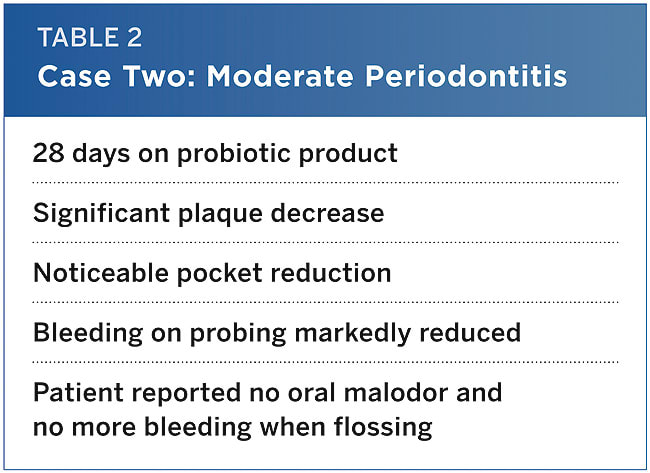

The second case involved a female patient with moderate periodontitis, who experienced noticeable reductions in probing depth and significant plaque reduction, without any additional home care instructions or adjunct home care tools. Bleeding on probing was markedly reduced. Consistent with the previous patient, she reported no oral malodor and no more bleeding when flossing (Table 2).

Patient Compliance and Motivation

It is challenging to motivate patients to successfully adopt recommended treatments that may clearly be in their interests. Dental professionals need to concentrate on being change agents, people whose behavior or deliberate actions result in behavioral changes in others. Bringing oral and overall health to the general public should be the main objective.

Patients may relate more positively to an explanation describing gingivitis as a treatable bacteria-related infection of the mouth that requires both professional and home care, rather than using the term periodontal disease. Patients who understand what they need to do to achieve and maintain health are more likely to adopt the recommended new behavior and comply with home care and return to the dental setting for treatment. This educational process involves learning how to motivate patients. Clinicians can use motivational interviewing, asking questions in a positive, nonthreatening way. “What is working with your home care?” If the patient’s reply indicates noncompliance, the dental professional can offer encouragement, reminding the patient that returning for the appointment is a positive step and they can again begin a joint plan to control plaque biofilm.

Clinicians can use the motivational interviewing (MI) model as a means to encourage behavioral change in patients. This model was initially developed for addiction counseling and has increasingly been applied to health promotion settings. A key goal of MI is to assist individuals to deal with their ambivalence about behavior change. It has shown to be particularly effective for individuals who are less inclined to be ready for change.9,10 Motivational interviewing is a method that enhances outcomes for compliance, employing a series of questions with an interested client. The core of this technique is a nonjudgmental encounter. This includes encouraging patients to express their own reasons for and against change, and thinking how their current behaviors and associated health status affect their core values and life preferences

Engaging patients by providing options in self-care regimens and allowing them to choose those that suit them best involves them proactively in oral healthcare. It is important to consider the taste of the product, whether it applies to the patient’s identified need, ease of use, cost, and published clinical evidence to determine its effectiveness. It is also essential that the patient is instructed in the correct use of the product according to the product label. Self-care selections should be recorded on patients’ charts for follow up during the next dental visit. Patients should then be asked about their experiences and if they followed the recommended oral hygiene regimen. Convincing patients to continue treatment beyond the initial stage is challenging. Patients may need to be reminded of the benefits they have reported (eg, reductions in bleeding and oral malodor). Dental professionals need to make the connection between what the patient has been told about infection and seeing patient results, such as reduced bleeding. This correlation may encourage the patient to continue treatment and self care. Having the dental professional note clinical improvements during the examination also re-enforces the positive message.

Conclusion

Probiotics, which act to maintain microbial balance, such as PerioBalance, may enhance clinical outcomes when incorporated into patients’ everyday oral healthcare regimen. It is important for dental professionals to educate their patients about these benefits through effectively communicated information, and to encourage compliance. Using proven motivational methods and placing special emphasis on a proactive patient role results in a total wellness approach to healthcare.

Disclosure

The author has received an honorarium from Sunstar Americas, Inc.

About the Author

Noel Kelsch, RDHAP

Speaker and Writer

Moorpark, California

References

1. Simauchi H, Mayanagi G, Nakaya S, et al. Improvement of periodontal condition by probiotics with Lactobacillus salivarius WB21: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35(10):897-905.

2. Teanpaisan R, Piwat S, Dahlén G. Inhibitory effect of oral Lactobacillus against oral pathogens [published online ahead of print July 31, 2011]. Lett Appl Microbiol. doi: 10.1111/1.1472-765X.2011.03132.x.

3. Riccia DN, Bizzini F, Perilli MG, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Lactobacillus brevis (CD2) on periodontal disease. Oral Dis. 2007;13(4):376-385.

4. Nase L, Hatakka K, Savilahti E, et al. Effect of long-term consumption of a probiotic bacterium, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG, in milk on dental caries and caries risk in children. Caries Res. 2001;35(6):412-420.

5. Krasse P, Carlsson B, Dahl C, et al. Decreased gum bleeding and reduced gingivitis by the probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri. Swed Dent J. 2006;30(2):55-60.

6. Twetman S, Derawi B, Keller M, et al. Short-term effect of chewing gum containing probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri on the levels of inflammatory mediators in gingival crevicular fluid. Acta Odontol Scand. 2009;67(1):19-24.

7. Nikawa H, Makihira S, Fukushima H, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri in bovine milk fermented decreases the oral carriage of mutans streptococci. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;95(2):219-223.

8. Caglar E, Cildir SK, Ergeneli S, et al. Salivary mutans streptococci and lactobacilli levels after ingestion of the probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 by straws or tablets. Acta Odontol Scand. 2006;64(5):314-318.

9. Butler C, Rollnick S, Cohen D, et al. Motivational consulting versus brief advice for smokers in general practice: A randomized trial. British Journal of General Practice. 1999;49:611-616.

10. Resnicow K, DiIorion C, Soet J, et al. Motivational Interviewing in medical and public health settings. In: Miller W, Rollnick S, eds. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002:251-269.